The

Phonograph and Its Future

Probability:

Books

.

Books. -- --

Books may be read by the charitably-inclined

professional reader, or by such readers especially employed for that

purpose, and the record of such book used in the asylums of the blind,

hospitals, the sick-chamber, or even with great profit and amusement

by the lady or gentleman whose eyes and hands may be otherwise employed;

or, again, because of the greater enjoyment to be had from a book

when read by an elocutionist than when read by the average reader.

The ordinary record-sheet, repeating this book from fifty to a hundred

times as it will, would command a price that would pay the original

reader well for the slightly-increased difficulty in reading it aloud

in the phonograph.

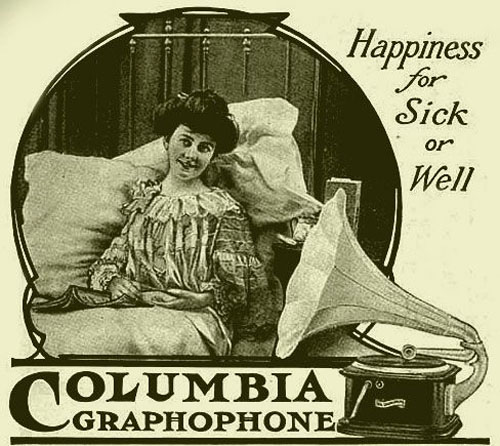

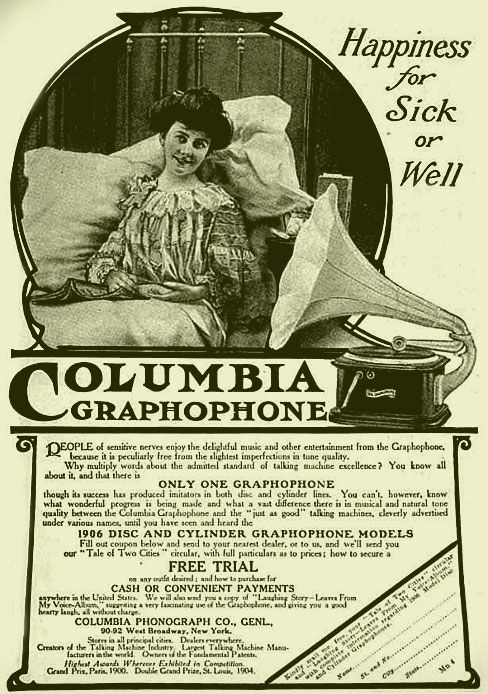

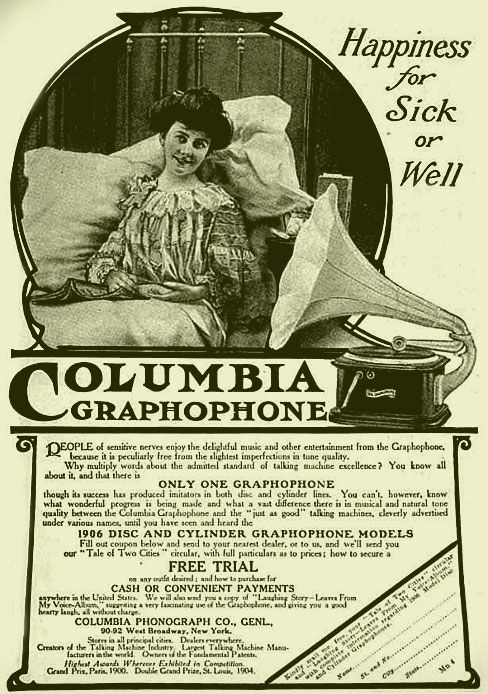

For the sick or well

1905 - Entertainment in

bed - Sick or Well

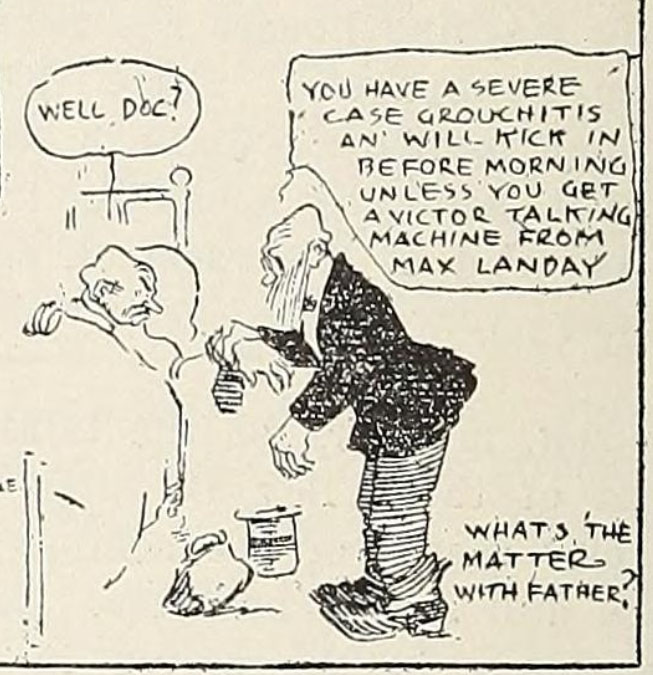

Doctor's prescription for

a severe case of grouchitis: a Victor Talking Machine

Panel from New York Review cartoon

promoting the Landay Bros. as the leading distributors of the Victor

Talking Machines and Records in Greater New York. (The

Talking Machine World,

July 1910).

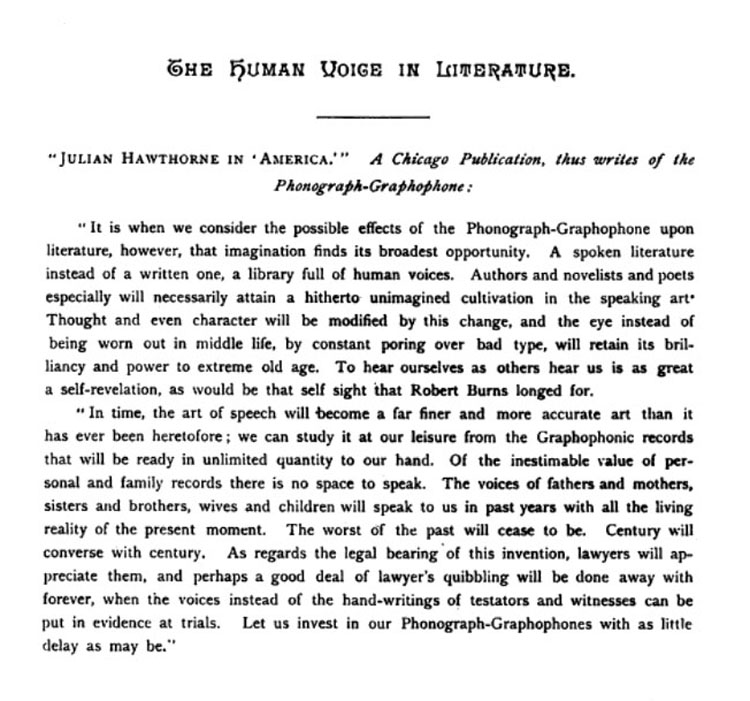

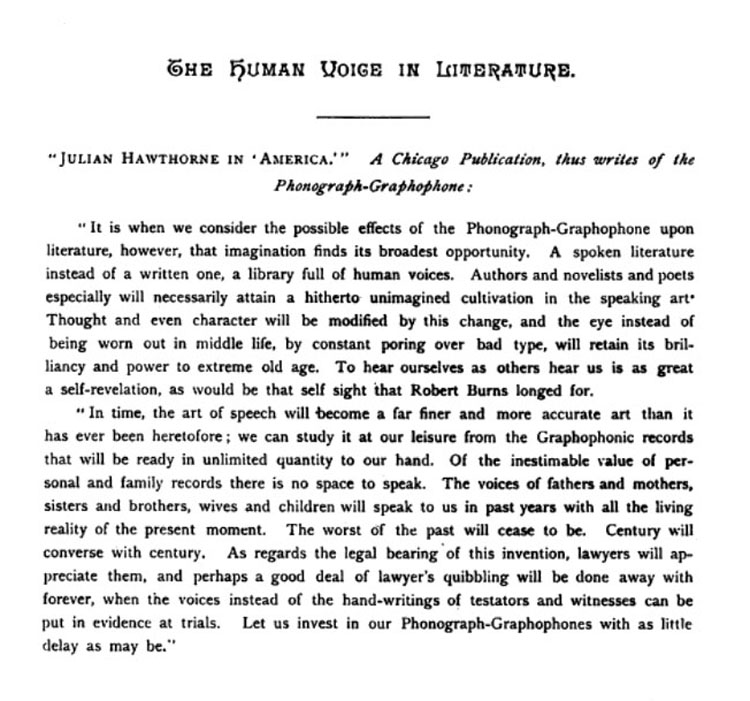

Julian Hawthorne, the son of Nathaniel

Hawthorne wrote in 1888 with enthusiasm about the phonograph's future

stating that its possible effects upon literature are where "imagination

finds its broadest opportunity. A spoken literature instead of a written

one, a library full of human voices...Let us invest in our Phonograph-Graphophones

with as little delay as may be."

"The Human Voice in

Literature" by Julian Hawthorne

Description of the

Phonograph and Phonograph-Graphophone by their Respective

Inventors-

Testimonials as to their

practical use, 1888, New York

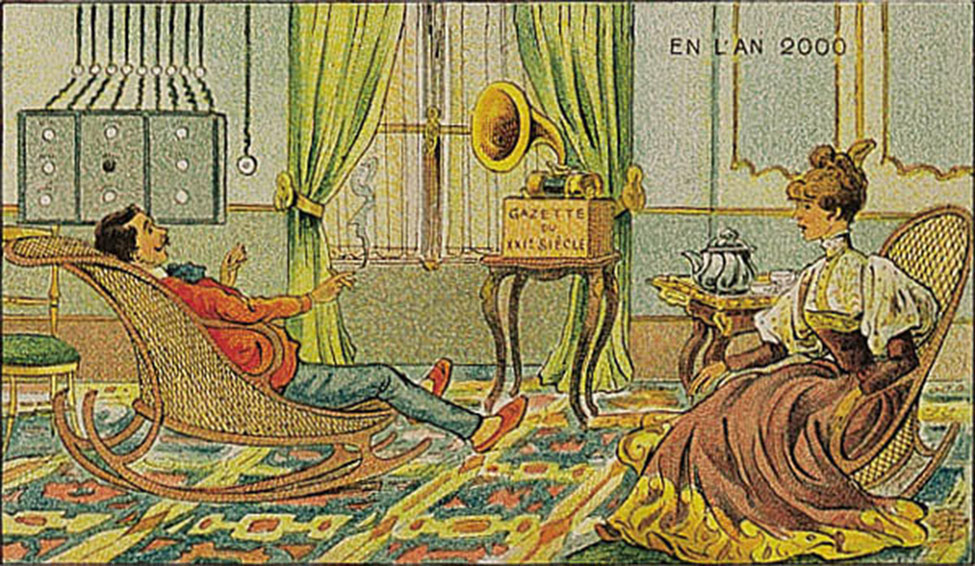

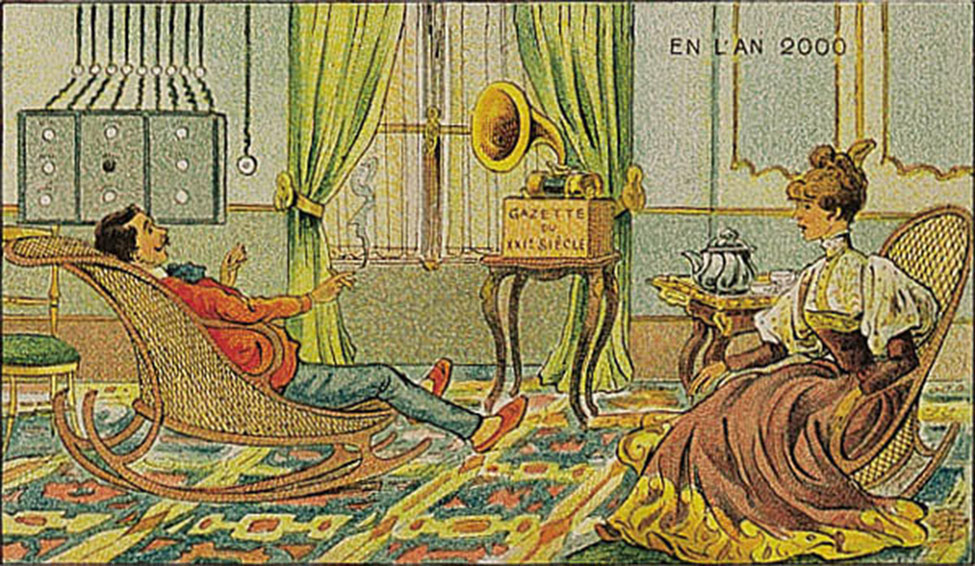

1910 postcard by Villemard

predicting how the newspaper will be heard on a phonograph record in

the year 2000.

Kiddie stories "told

in the author's own voice." Columbia records, The Talking

Machine World, March 15, 1918

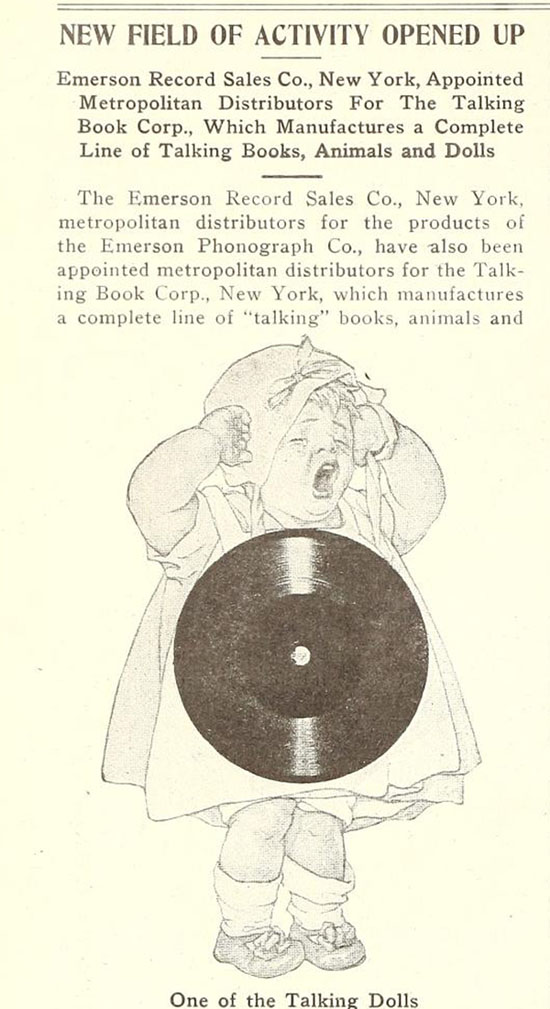

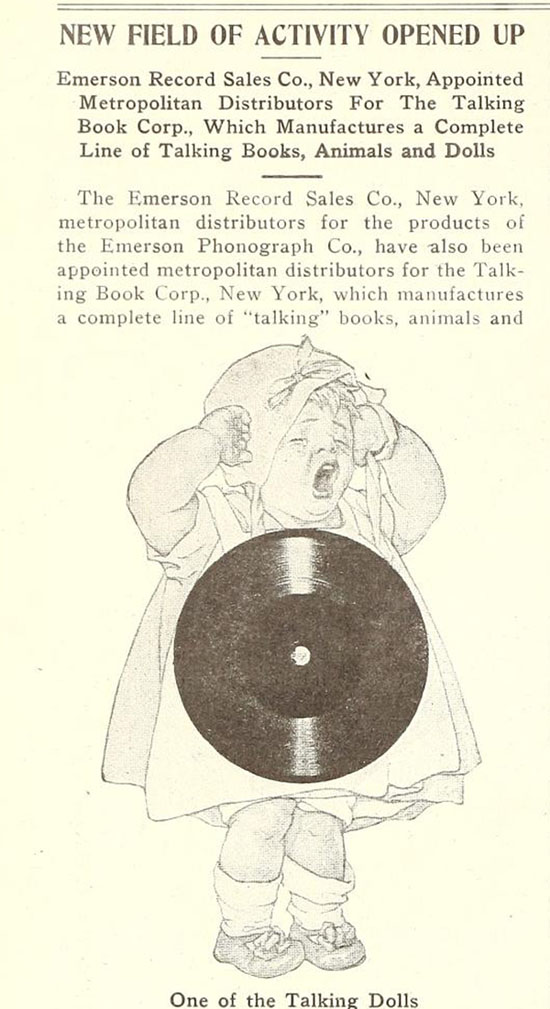

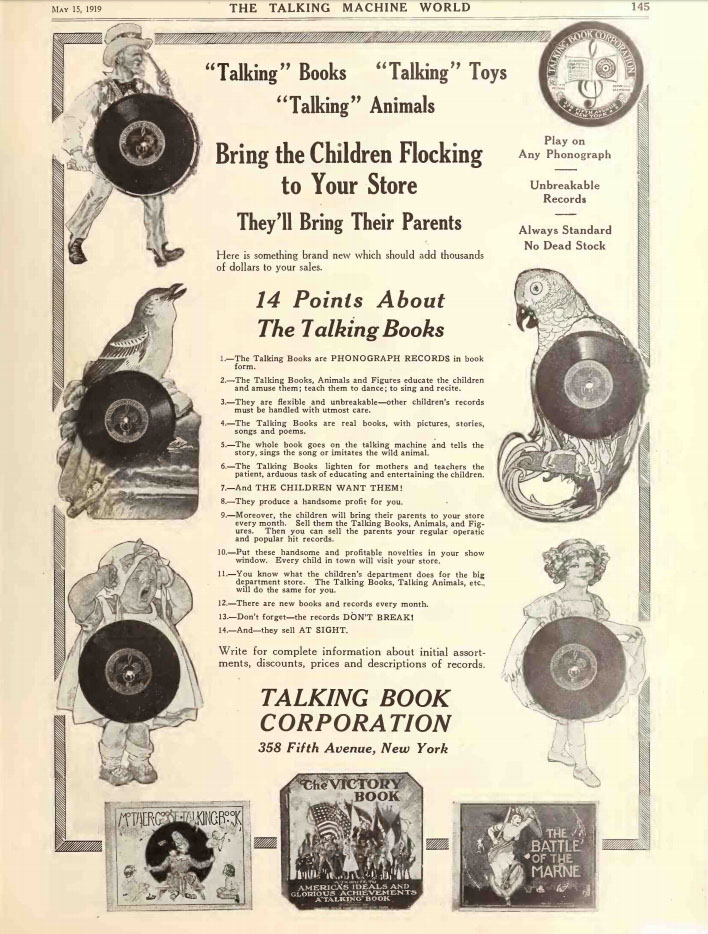

The

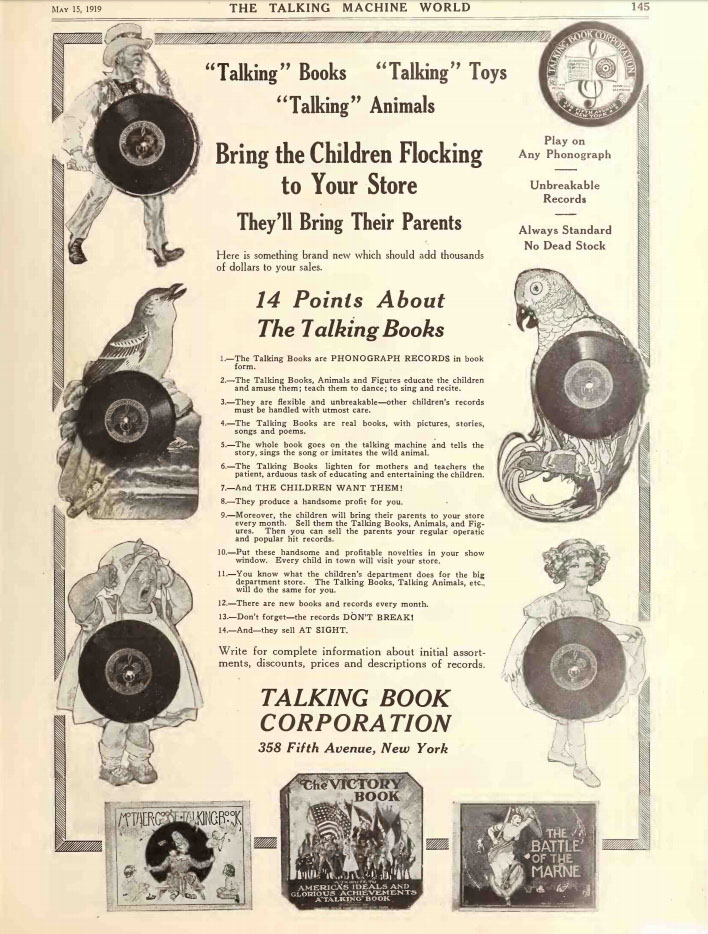

Talking Machine World, May 15, 1919

The Talking Machine

World, May 15, 1919

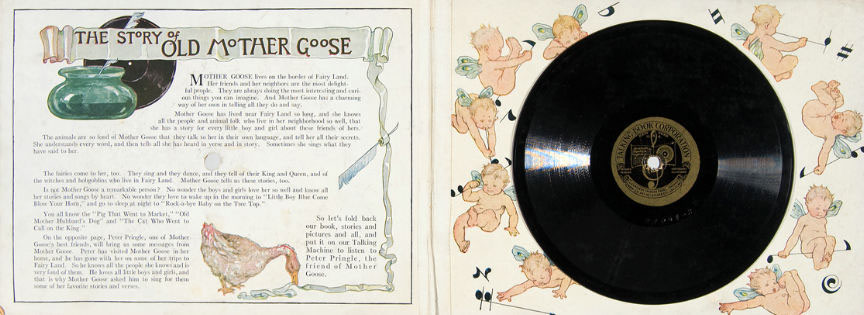

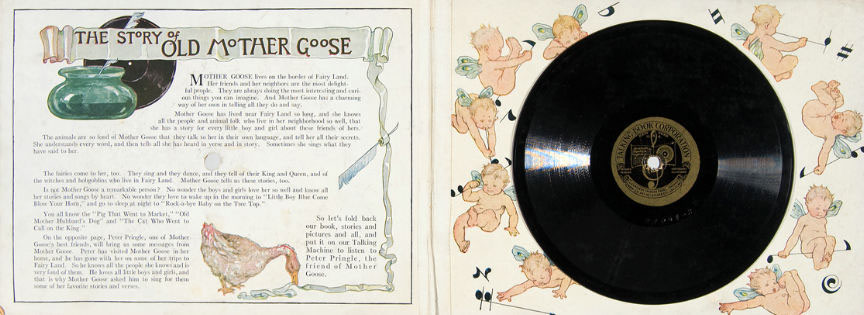

Published by Talking Book

Corporation, Illustrated by C.M. Burd

Inside cover of Mother

Goose Talking Book.

The Mocking Bird -

Talking Book Corporation 1918

The Tired Baby -

Talking Book Corporation 1919. Played "Sleep, Baby, Sleep" 78 rpm.

For more examples of Talking Book Corp. records from this series, see Discogs.

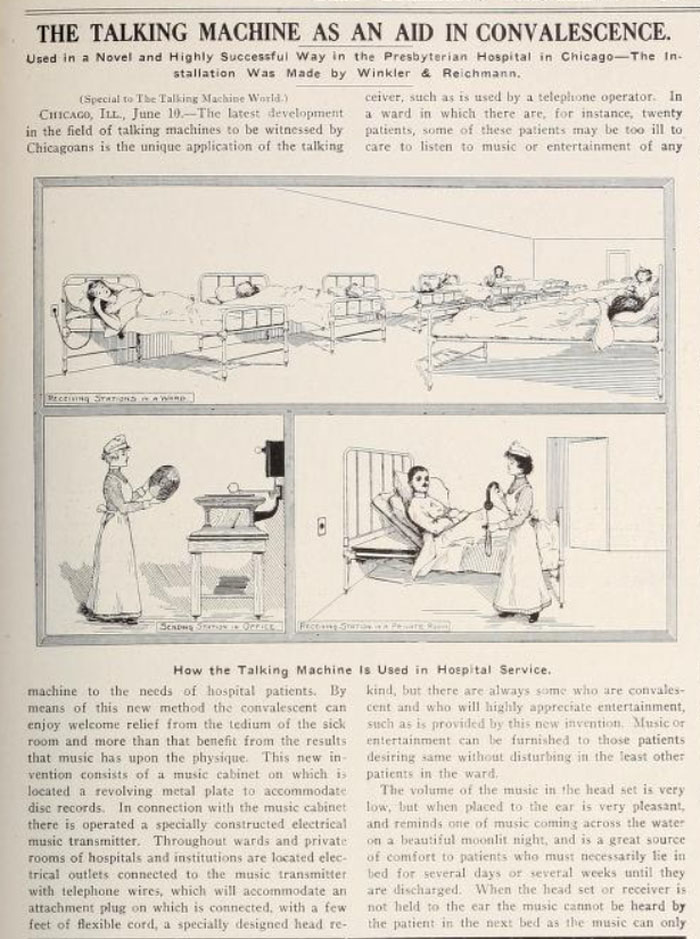

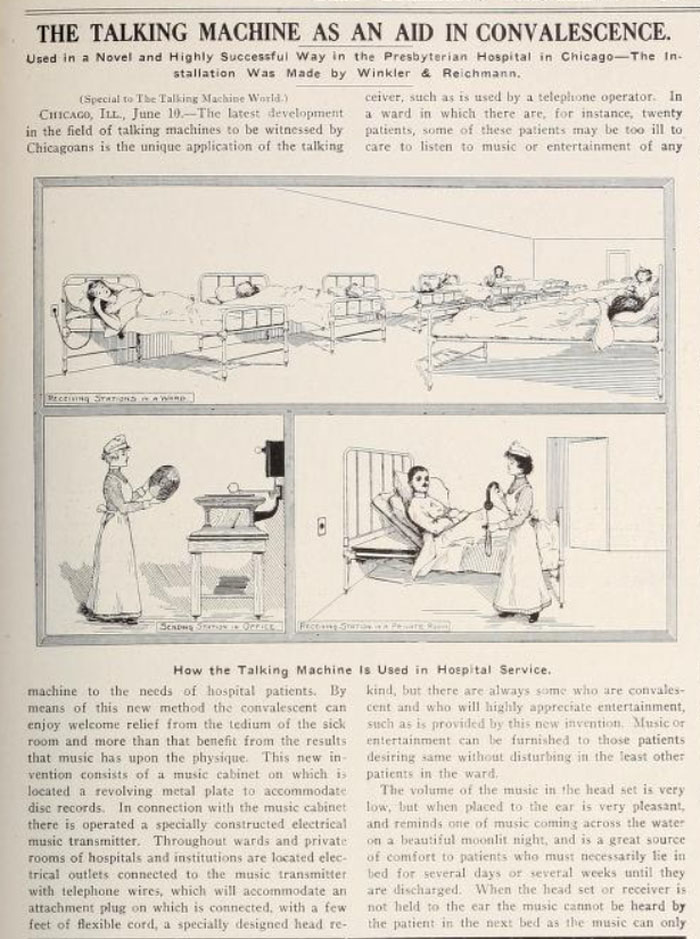

"Relief from the Tedium of the Sick

Room" with music from the Talking Machine.

The Talking Machine

World, June 1915

Library of Congress

authorized in 1931 to administer books for those with vision loss

"The Pratt-Smoot Act of March 1931

authorized the Library of Congress to administer a project in which

selected libraries would "serve as local or regional centers for the

circulation of books" to adults with vision loss. Eighteen libraries

were chosen to distribute the books, and the Library of Congress selected

fifteen titles to be brailled. This was the beginning of the National

Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped." See

the American Foundation for the Blind AFB

for details of confidential letter suggesting the use of phonograph

records and the authorization of funds in 1933 for talking books.

"We will not only have to

build up a library of phonograph records, but we will have to provide

thousands of blind people with inexpensive talking machines."

The legal question that also must be answered "is whether

a book is still a book when it is printed on phonograph records."

Here is some history of the "Talking

Books" project as described on the National

Library Services webpage (1):

"Finally, in 1933, AFB produced

two types of machines – one spring driven and the other a combination

electric radio and phonograph. A durable record was perfected, recorded

at 150 grooves to an inch, so that a book of 60,000 words could

be contained on eight or nine double-faced, twelve-inch records.

The turntable ran at 33-1/3 revolutions per minute, which permitted

thirty minutes of reading time on each record. By 1934, the talking

book was developed and the number of reproducers in the hands of

blind readers was sufficient to justify using part of the congressional

appropriation for purchasing records." (1)

"The 1934 annual report of

the Librarian of Congress, the Library's first order was for the

following titles:

The Four Gospels

The Psalms

Selected Patriotic Documents:

Declaration of Independence and Constitution

of the United States Washington's Farewell Address and Washington's

Valley Forge Letter to the Continental Congress. Lincoln's Gettysburg

Address, Lincoln's First and Second Inaugural Addresses.

Collection of Poems

Shakespeare:

As You Like It, Merchant of Venice,

Hamlet, Sonnets.

Fiction: Carroll: As the Earth

Turns Delafield: The Diary of a Provincial Lady Jarrett:

Night Over Fitch's Pond Kipling: The Brushwood Boy Masefield:

The Bird of Dawning Wodehouse: Very Good, Jeeves."

(list from Chapter 10, The

Talking Book, AFB)

"The Library’s appropriation

did not at first include funds for machines; they had to be purchased

at a cost between thirty-five and sixty dollars, either by the blind

person who desired to borrow the recorded books or on his behalf

(as was frequently the case) by philanthropic organizations."

(1)

Robert B. Irwin, AFB Executive

Director, demonstrates the Talking Book machine to Helen Keller

in the Helen Keller Room at AFB (photograph courtesy of Talking

Book Archives, American Foundation for the Blind. Circa December

1935)

Photo courtesy of The National Library

Service for the Blind and Print Disabled

"In spring 1962 the Library

of Congress began ordering talking books for juveniles recorded

on ten-inch records at 16-2/3 rpm, and all talking-books ordered

after January 1963 were recorded on 16-2/3 rpm records. This smaller,

slower-speed disc provided forty-five minutes of recorded time on

each side of the record, thus reducing the number of records required

for each book. The savings effected by the change of speed were

used to increase the number of copies of each talking book that

could be produced and to add five popular magazines to the talking-book

program.

In 1969, magazines began to be

recorded at 8-1/3 rpm, and the recording of all disc talking books

at 8-1/3 rpm began in January 1973. Use of these slow recording

speeds made it possible to include almost twice as much material

as on a disc of corresponding size recorded at 16-2/3 rpm. Savings

thus effected allowed for an increase in the number of copies issued

for each title selected. Since fewer records were required for each

book, readers and librarians could handle, store, and ship the ten-inch,

8-1/3 rpm records much more easily and economically than the larger,

bulkier records." (1)

An excellent timeline and Chronology

of Developments in the National Program is also on the NLS

webpage.

Examples of Digital Audio

Books available in 2020 for free from National Library Service

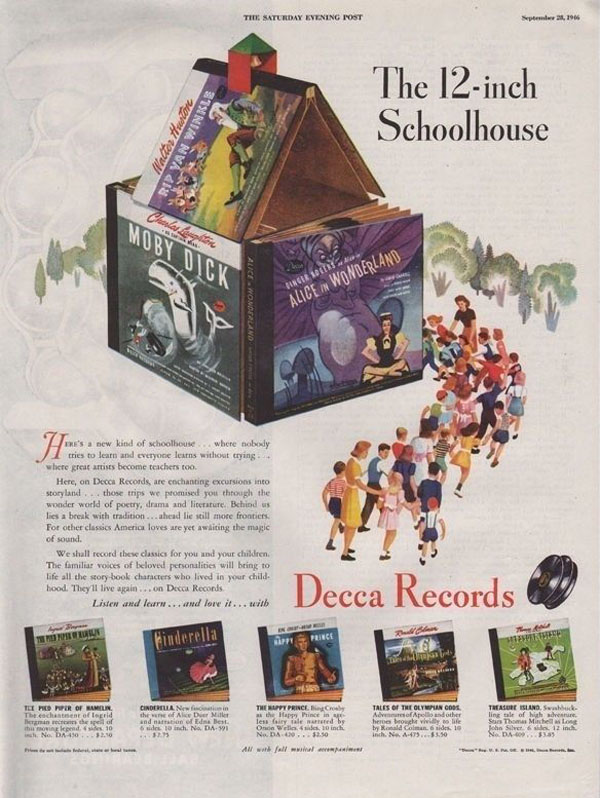

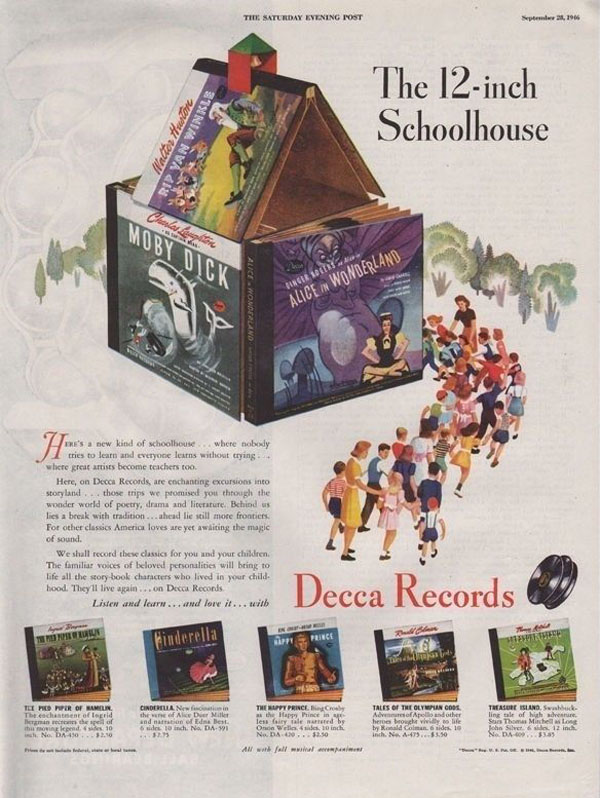

"Enchanting excursions into storyland..." read by "familiar

voices of beloved personalities..."

The Saturday Evening

Post, 1946

Phonographia

|