Mr.

Thomas A. Edison recently came into this office, placed a little

machine on our desk, turned a crank, and the machine inquired as

to our health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that

it was very well, and bid us a cordial good night. These remarks

were not only perfectly audible to ourselves, but to a dozen or

more persons gathered around, and they were produced by the aid

of no other mechanism than the simple little contrivance explained

and illustrated below.

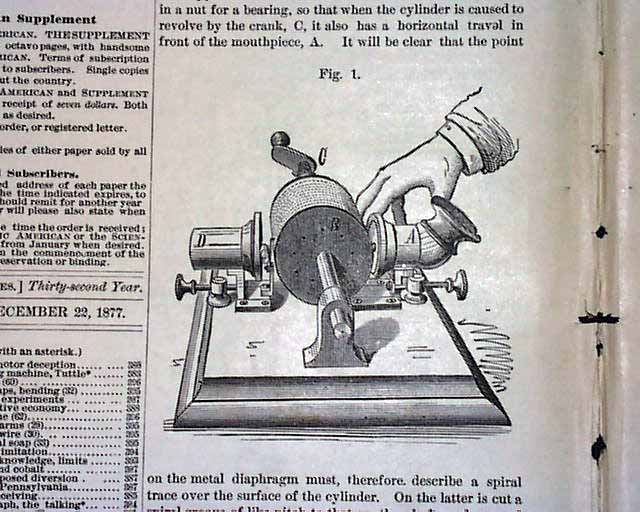

The

principle on which the machine operates we recently explained quite

fully in announcing the discovery. There is, first, a mouth piece,

A, Fig. 1, across the inner orifice of which is a metal diaphragm,

and to the center of this diaphragm is attached a point, also of

metal. B is a brass cylinder supported on a shaft which is screw-threaded

and turns in a nut for a bearing, so that when the cylinder is caused

to revolve by the crank, C, it also has a horizontal travel in front

of the mouthpiece, A. It will be clear that the point on the metal

diaphragm must, therefore, describe a spiral trace over the surface

of the cylinder. On the latter is cut a spiral groove of like pitch

to that on the shaft, and around the cylinder is attached a strip

of tinfoil. When sounds are uttered in the mouthpiece, A, the diaphragm

is caused to vibrate and the point thereon is caused to make contacts

with the tinfoil at the portion where the latter crosses the spiral

groove. Hence, the foil, not being there backed by the solid metal

of the cylinder, becomes indented, and these indentations are necessarily

an exact record of the sounds which produced them.

It

might be said that at this point the machine has already become

a complete phonograph or sound writer, but it yet remains to translate

the remarks made. It should be remembered that the Marey and Rosapelly,

the Scott, or the Barlow apparatus, which we recently described,

proceed no further than this. Each has its own system of caligraphy

[sic], and after it has inscribed its peculiar sinuous lines it

is still necessary to decipher them. Perhaps the best device of

this kind ever contrived was the preparation of the human ear made

by Dr. Clarence J. Blake, of Boston, for Professor Bell, the inventor

of the telephone. This was simply the ear from an actual subject,

suitably mounted and having attached to its drum a straw, which

made traces on a blackened rotating cylinder. The difference in

the traces of the sounds uttered in the ear was very clearly shown.

Now there is no doubt that by practice, and the aid of a magnifier,

it would be possible to read phonetically Mr. Edison's record of

dots and dashes, but he saves us that trouble by literally making

it read itself. The distinction is the same as if, instead of perusing

a book ourselves, we drop it into a machine, set the latter in motion,

and behold! the voice of the author is heard repeating his own composition.

The

reading mechanism is nothing but another diaphragm held in the tube,

D, on the opposite side of the machine, and a point of metal which

is held against the tinfoil on the cylinder by a delicate spring.

It makes no difference as to the vibrations produced, whether a

nail moves over a file or a file moves over a nail, and in the present

instance it is the file or indented foil strip which moves, and

the metal point is caused to vibrate as it is affected by the passage

of the indentations. The vibrations, however, of this point must

be precisely the same as those of the other point which made the

indentations, and these vibrations, transmitted to a second membrane,

must cause the latter to vibrate similar to the first membrane,

and the result is a synthesis of the sounds which, in the beginning,

we saw, as it were, analyzed.

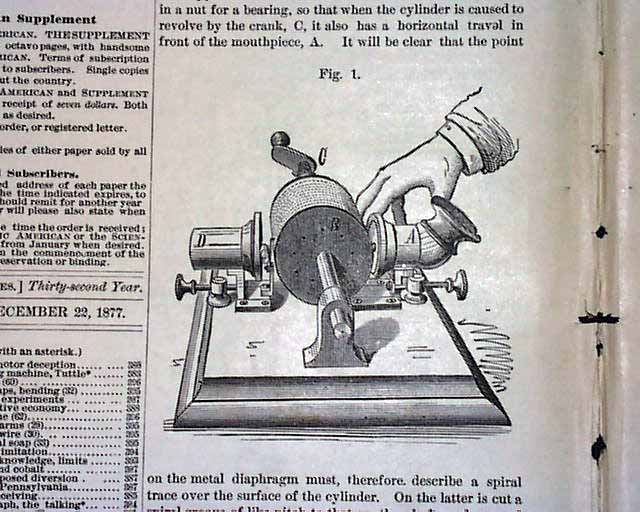

In

order to exhibit to the reader the writing of the machine which

is thus automatically read, we have had a cast of a portion of the

indented foil made, and from this the dots and lines in Fig. 2 are

printed in of course absolute facsimile, excepting that they are

level instead of being raised above or sunk below the surface. This

is a part of the sentences, "How do you do?" and "How do you like

the phonograph?" It is a little curious that the machine pronounces

its own name with especial clearness. The crank handle shown in

our perspective illustration of the device does not rightly belong

to it, and was attached by Mr. Edison in order to facilitate its

exhibition to us.

In

order that the machine may be able exactly to reproduce given sounds,

it is necessary, first, that these sounds should be analyzed into

vibrations, and these registered accurately in the manner described;

and second, that their reproduction should be accomplished in the

same period of time in which they were made, for evidently this

element of time is an important factor in the quality and nature

of the tones. A sound which is composed of a certain number of vibrations

per second is an octave above a sound which registers only half

that number of vibrations in the same period. Consequently if the

cylinder be rotated at a given speed while registering certain tones,

it is necessary that it should be turned at precisely that same

speed while reproducing them, else the tones will be expressed in

entirely different notes of the scale, higher or lower than the

normal note as the cylinder is turned faster or slower. To attain

this result there must be a way of driving the cylinder, while delivering

the sound or speaking, at exactly the same rate as it ran while

the sounds were being recorded, and this is perhaps best done by

well regulated clockwork. It should be understood that the machine

illustrated is but an experimental form, and combines in itself

two separate devices--the phonograph or recording apparatus, and

the receiving or talking contrivance which reads it. Thus in use

the first machine would produce a slip, and this would for example

be sent by mail elsewhere, together in all cases with information

of the velocity of rotation of the cylinder. The recipient would

then set the cylinder of his reading apparatus to rotate at precisely

the same speed, and in this way he would hear the tones as they

were uttered. Differences in velocity of rotation within moderate

limits would by no means render the machine's talking indistinguishable,

but it would have the curious effect of possibly converting the

high voice of a child into the deep bass of a man, or vice versa.

No

matter how familiar a person may be with modern machinery and its

wonderful performances, or how clear in his mind the principle underlying

this strange device may be, it is impossible to listen to the mechanical

speech without his experiencing the idea that his senses are deceiving

him. We have heard other talking machines. The Faber apparatus for

example is a large affair as big as a parlor organ. It has a key

board, rubber larynx and lips, and an immense amount of ingenious

mechanism which combines to produce something like articulation

in a single monotonous organ note. But here is a little affair of

a few pieces of metal, set up roughly on an iron stand about a foot

square, that talks in such a way, that, even if in its present imperfect

form many words are not clearly distinguishable, there can be no

doubt but that the inflections are those of nothing else than the

human voice.

We

have already pointed out the startling possibility of the voices

of the dead being reheard through this device, and there is no doubt

but that its capabilities are fully equal to other results just

as astonishing. When it becomes possible as it doubtless will, to

magnify the sound, the voices of such singers as Parepa and Titiens

will not die with them, but will remain as long as the metal in

which they may be embodied will last. The witness in court will

find his own testimony repeated by machine confronting him on cross-examination--the

testator will repeat his last will and testament into the machine

so that it will be reproduced in a way that will leave no question

as to his devising capacity or sanity. It is already possible by

ingenious optical contrivances to throw stereoscopic photographs

of people on screens in full view of an audience. Add the talking

phonograph to counterfeit their voices, and it would be difficult

to carry the illusion of real presence much further.