Bottling

Up Sound for Future Use

Punch’s Almanack

for 1878, December 14, 1877

By Doug Boilesen, 2020

The invention of the phonograph

would result in various ways the public could think about the

phonograph's fundamental and revolutionary ability to capture

sound for future use. The following are examples of some of

those metaphors and phrases that appeared in print to describe

the wonder of recorded sound, e.g., bottled sound, "canned

music," imprisoned sound, gathered up and retained sounds,

captured sound, etc.

Bottled

Sound

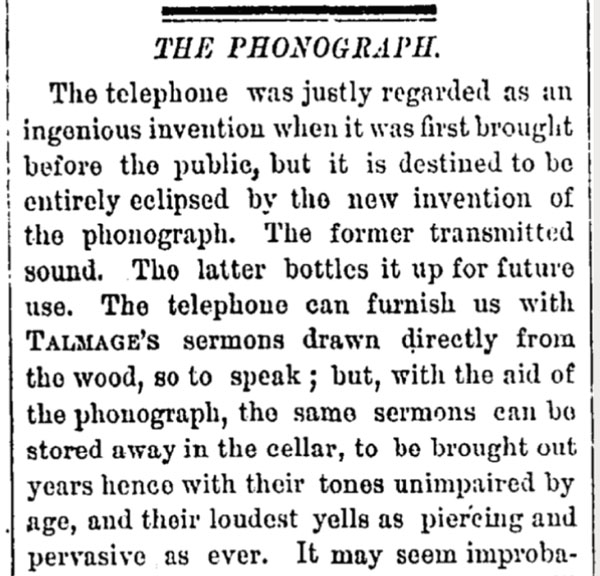

The New York Times

on November 7, 1877, responding to the announcement that Edison's

phonograph would soon be a reality, wrote an article starting with

the statement that the phonograph "was destined" to entirely

eclipse the ingenious telephone which only transmitted sound whereas

the phonograph "bottles it up for future use."

The New York Times

on November 7, 1877,

.

This article, however, was written

one month before Edison actually completed his phonograph and six

months before Edison would publish his own probabilities about the

future of the phonograph so enthusiasm, speculation and skepticism

were choices for how the press might present this impending invention.

In their November 7, 1877 article

The New York Times chose skepticism and a bit of sarcasm

by using bottling up sound as their metaphor and then by providing

examples in the extreme of what that bottling up of sound would

eliminate or change. If a phonograph can bottle sound then

"Why should we print a speech

when it can be bottled?"

Why should we learn to read when

novels can be listened to "without taking the slightest trouble?"

Instead we "shall be able to

buy Dickens and Thackeray by the single bottle or by the dozen."

"Instead of libraries

with combustible books, we shall have vast storehouses of bottled

authors, and though students in college may be required to learn

the use of books, just as they now learn the dead languages, they

will not be expected to make any practical use of the study."

"Blessed will be the lot of

the small boy of the future" who will never have to learn

his letters or wrestle with the spelling-book..."

.

The New York Times

on November 7, 1877

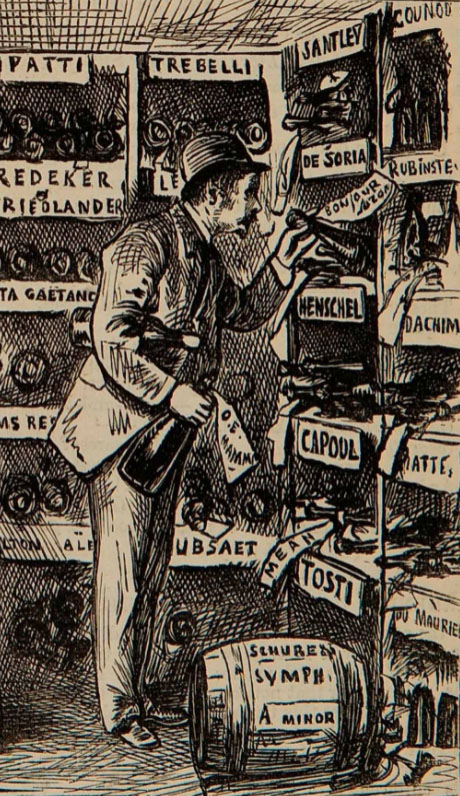

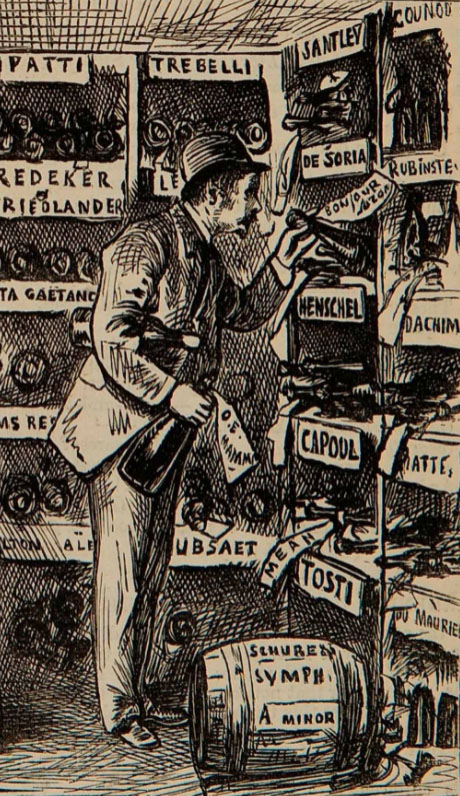

Besides bottling up authors and books

the phonograph would also be able to bottle up opera stars and music

as shown in this engraving from Punch’s Almanack for 1878,

December 14, 1877 (1)

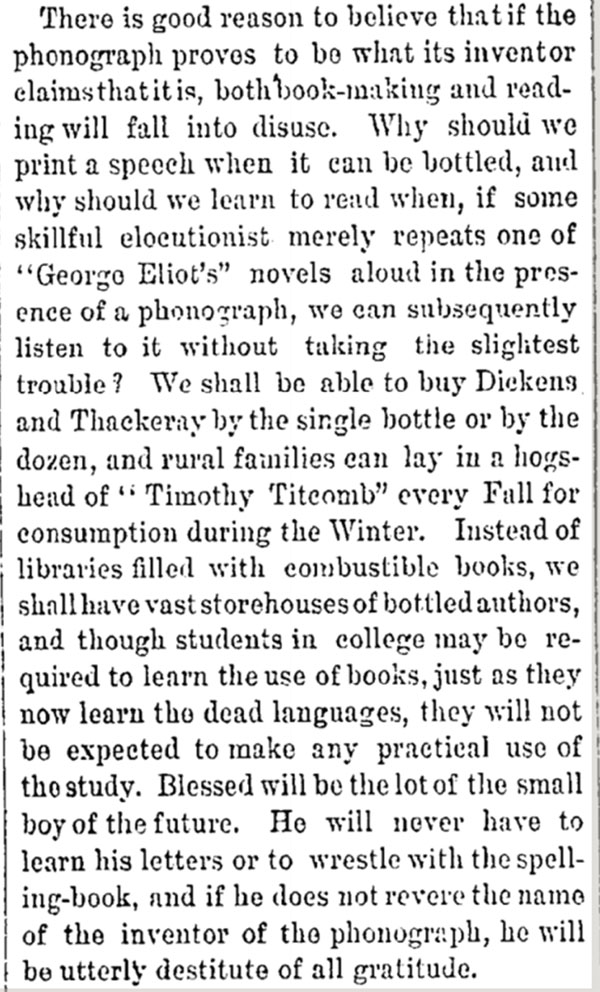

"Bottled Music"

In The Phonoscope, January

1891, an article titled "Bottled Music" noted that the

U.S. Marine Band's music was "having its most harmonious

strains bottled in large quantities."

The Phonoscope,

January 1891

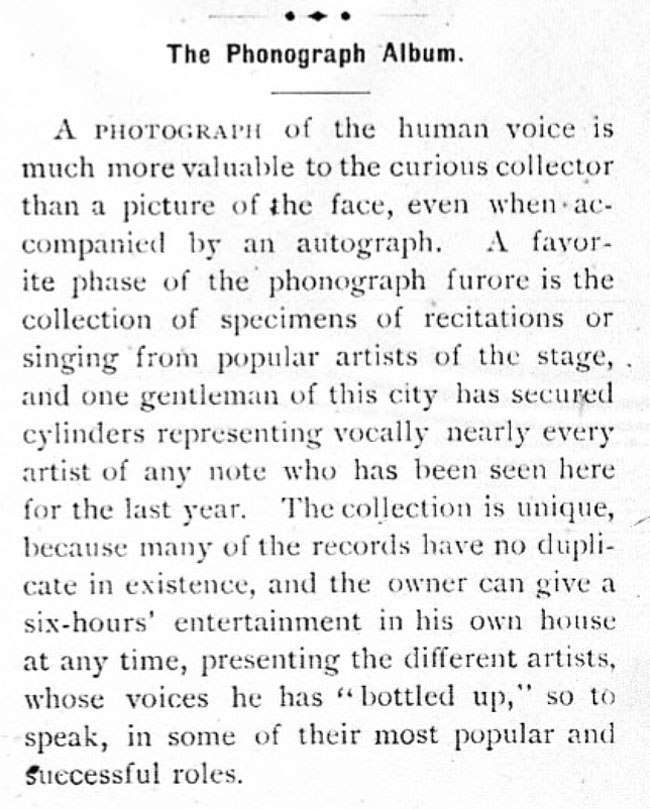

The Phonoscope,

February 1891, in an article titled "The Phonograph Album"

observed how a phonograph collection of recitations and popular

artists of the stage could allow its owner to give a "six-hours'

entertainment in his own house at any time, presenting the different

artists, whose voices he has "bottled up," so to speak,

in some of their most popular and successful roles."

"The Bettini device knows all

languages" Also, "bottled in the studio for future

uncorking is the music..."

The Phonoscope,

December 1899

Artists

Voices "Bottled Up"

The Phonoscope,

February 1891

Although The New York Times

description of the phonograph being like wine bottled up for the

future was a clever metaphor, the article actually missed a fundamental

aspect of what the phonograph could do. It was stated that whatever

was "stored away in the cellar" could be brought out years

hence. But the Phonograph could do much more than simply store something

like a bottle of wine that could be drunk at a later time. What

was missing was the wonder that captured sound could be enjoyed

by anyone, anywhere and as often as they wanted -- and the fact

that the bottle would always remain full.

In keeping with this "bottling"

description for recorded sound John Philip Sousa would write some

disparaging remarks about recorded music using a different container

and calling it "canned music." Like a bottle, a can is

a container that can be filled with something and then emptied.

In his 1906 article in Appleton's Magazine titled "The

Menance of Mechanical Music" Sousa made his case against 'canned

music" which he feared was becoming a “substitute for human

skill, intelligence and soul.”

Canned music is "going

to ruin the artistic development of music in this country. When

I was a boy...in front of every house in the summer evenings, you

would find young people together singing the songs of the day or

old songs. Today you hear these infernal machines going night and

day. We will not have a vocal cord left. The vocal cord will be

eliminated by a process of evolution, as was the tail of man when

he came from the ape."

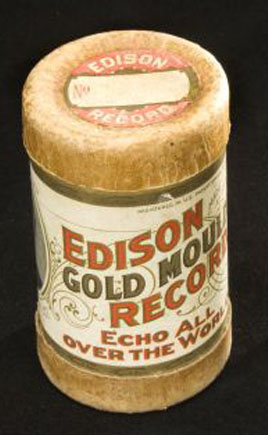

Circa 1904 Edison cylinder

record stored in cylinder box, similiar to an early 1900 can of baking

powder.

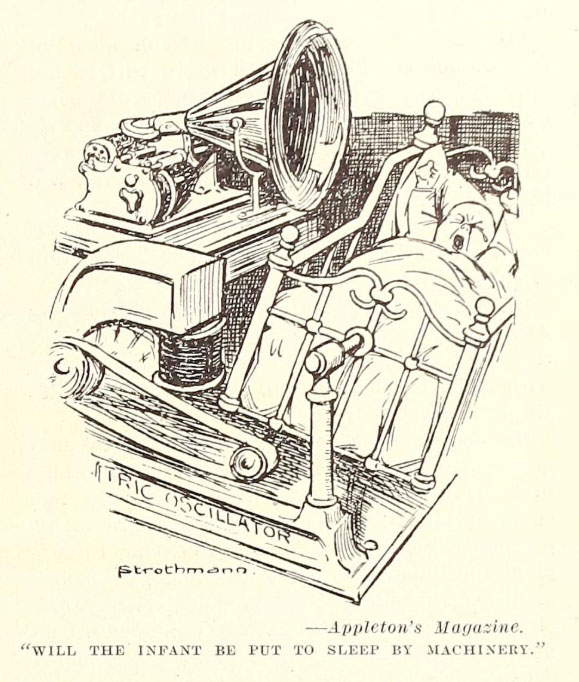

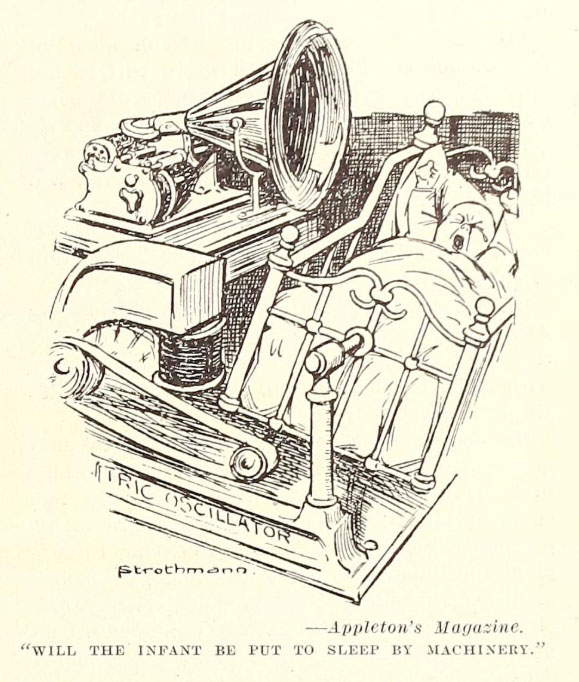

Some of Sousa's fears

about "canned music" illustrated

.

Appleton's

Magazine,

"The Menace of Mechanical Music" by John Philip Sousa, September

1906

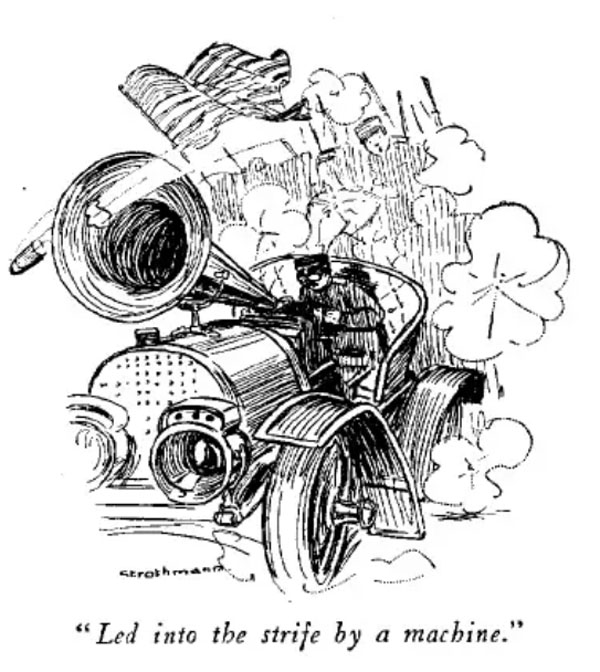

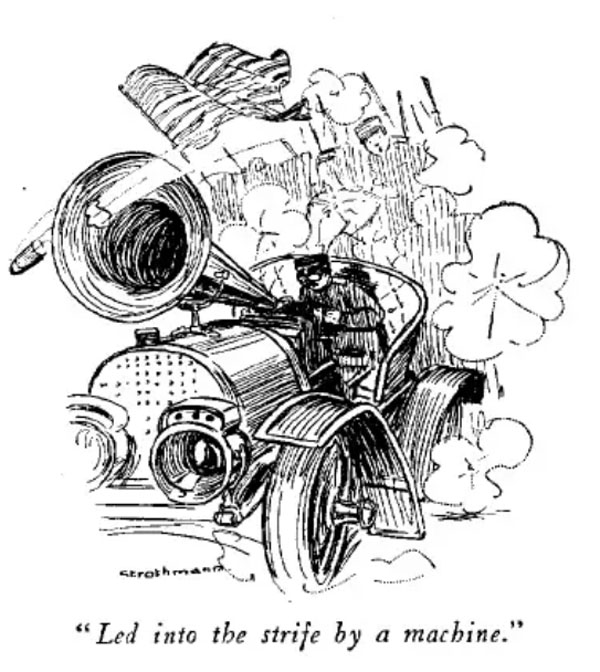

Asked Sousa: "Shall

we not expect that when the nation once more sounds its call to

arms and the gallant regiment marches forth, there will be no majestic

drum major, no serried ranks of sonorous trombones, no glittering

array of brass, no rolling of drums? In their stead will be a huge

phonograph, mounted on a 100 H. P. automobile, grinding out "The

Girl I Left Behind Me," "Dixie," and "The Stars

and Stripes Forever."

A 1906 Response to Sousa by the

New York Evening Post

'Canned music' is the epithet

applied by Mr. Sousa to the music made by phonographs and 'piano-players.'

He strongly objects to it on the ground that it tends to blunt

our national music sense. But it is a little difficult to see

what there is to blunt in the musical sense of a nation which

makes a hero of a Sousa, paying him $50,000 for a mediocre march

not worth $50. The phonographs help to make life more worth living

to farmers and villagers. They are not on a high aesthetic level,

but neither are the Sousa pieces, which are the favorites of the

phonograph audiences.

New York Evening Post, September

8, 1906

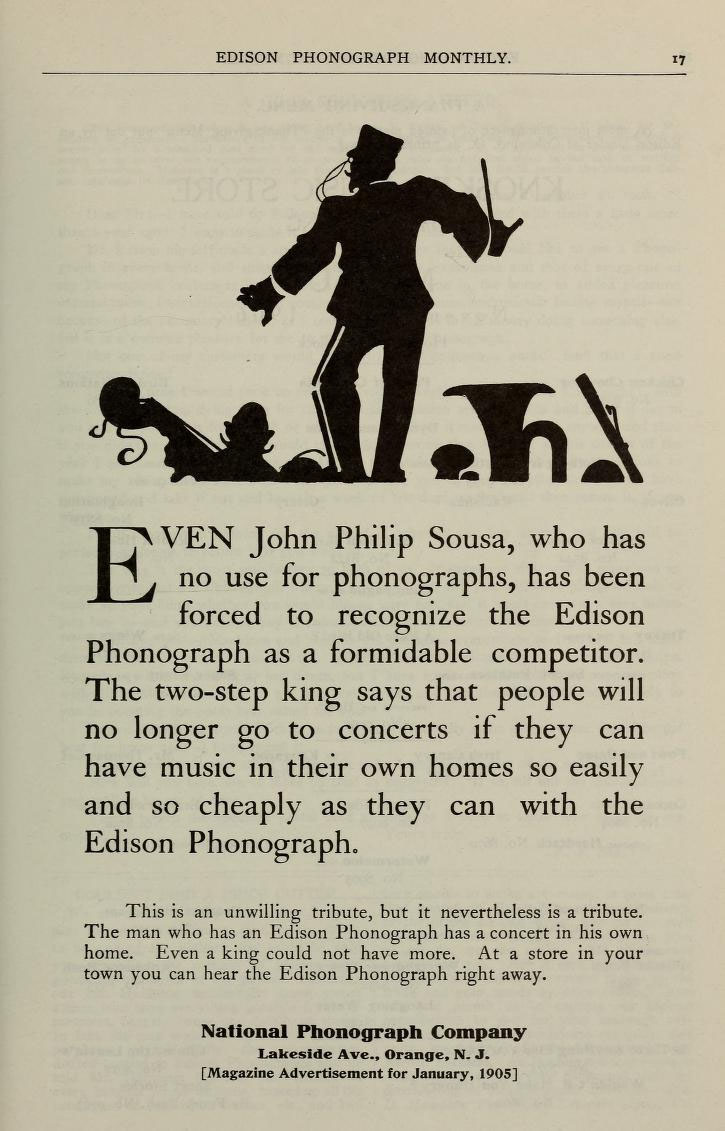

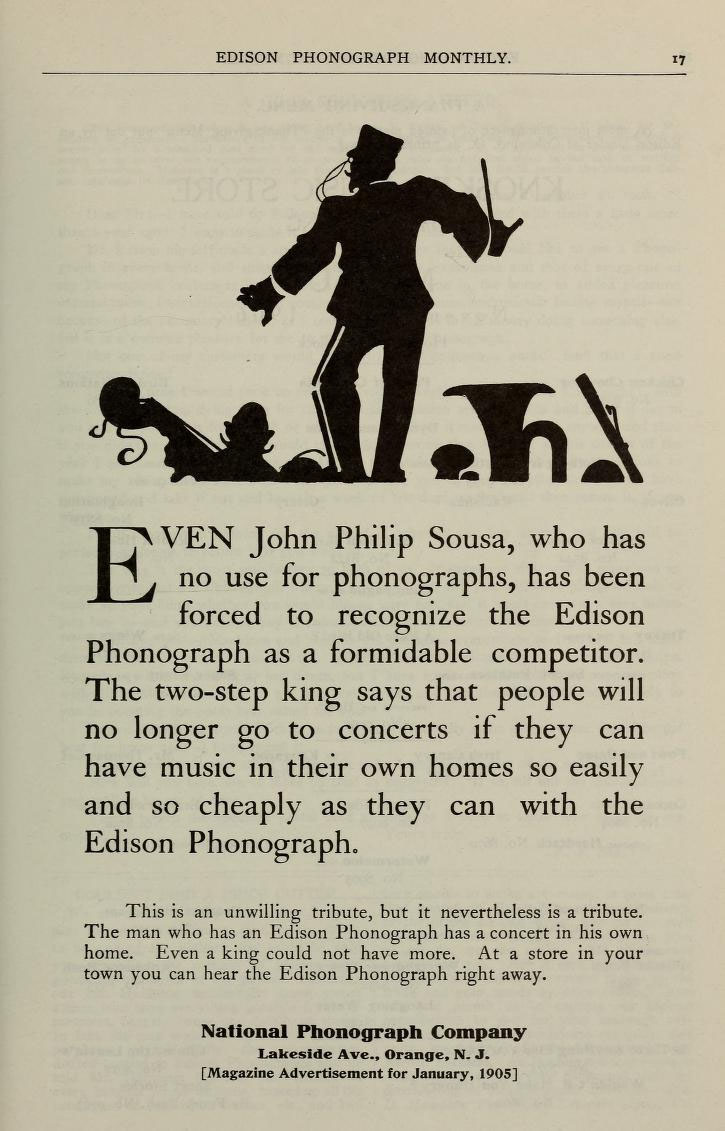

An advertising response

by Edison to Sousa's complaints about the phonograph and "canned

music."

The Edison Phonograph

Monthly, January 1907

.

An earlier use of "canned

music" had appeared in O. Henry's 1904 story "The

Phonograph and the Graft." In addition to calling phonograph

music "canned" Henry also described the phonograph and its

records as "our galvanized prima donna and correct imitations

of Sousa's band excavating a march from a tin mine."

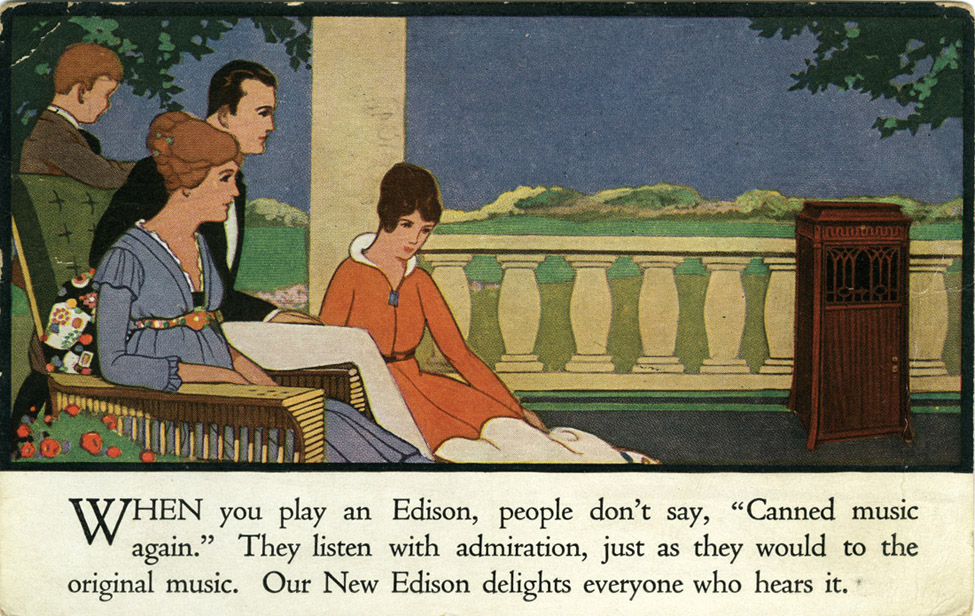

This Edison dealer postcard

advertising The New Edison (c. 1917) challenged previous generation

disparagements that talking machines play 'canned music." The

Edison did not play "canned music" - everyone who hears

the New Edison will delight in admiration, "just as they would

to the original music." (PM-0708)

"Canned Speech"

See Phonographia's Dictionary of

Phonographia for the definition of "Canned

Speech."

Celebrity and political impersonation

speeches (e.g., McKinley original Speech is what Brainey is currently

recording) Judge, June 1897 (PM-1825)

The "canned speech"

of President Wilson

May 24, 1913, Lincoln

Daily News

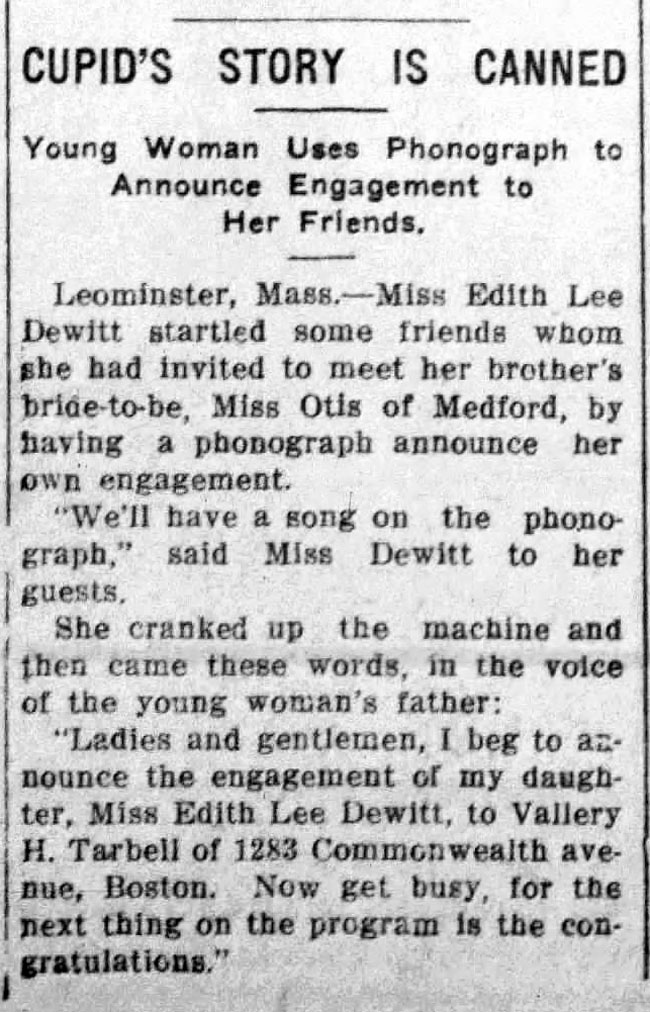

"Canned Engagement

Annoucement"

The Nebraska State Democrat,

May 16, 1912

"Imprison Sound"

Oakland Daily Evening Tribune,

May 1, 1878 reported that "It has been demonstrated beyond a doubt

that the phonograph, as perfected by Edson (sic), can imprison sound

and let it out at any future time."

Its summary for future use included the following: Testify in divorce

cases ("The phonograph won't lie."); send it to church on a rainy

Sunday to bring home the music and the sermon; repeat a good concert

at home. "But as a revealer of family secrets the phonograph may yet

lay the mischief. It will talk too much. The world has gained immensely,

because an infinite amount of mischievous talk has gone into oblivion.

But if hereafter, the phonograph is to be used as a repeater, a great

many lips would need to be toned to prudent speech."

"gathering up and

retaining of sounds..."

The opening paragraph of Edison's 1878

article, "The Phonograph and its Future" (The North American

Review May-June 1878), identified the foundation principle of

Edison's Phonograph as "the gathering up and retaining of sounds

hitherto fugitive, and their reproduction at will." This description

of sound as previously 'fugitive' is repeating the language of the

Oakland Tribune's pronouncement that sound can now be imprisoned.

The cultural change in the perception of sound and its preservation

was the revolution of the phonograph. Ephemeral sound would be forever

changed.

"capture the

fleeting beauties" of sound

This 1918 Victor advertisement dramatically

contrasts how the phonograph has changed music and the perception

of sound forever. On stage the ghost of Jenny Lind stands behind Melba

and the message of the ad is poignant and clear: "Jenny Lind

is only a memory but the voice of Melba can never die." Melba's

voice can be heard anytime, any place and as often as you want, flowing

forever "in centuries to come."

"Practically every great

singer and instrumentalist of this generation makes records only for

the Victor--thus perpetuating their art for all time. Life,

1918. (PM-2008)

Phonographia

|