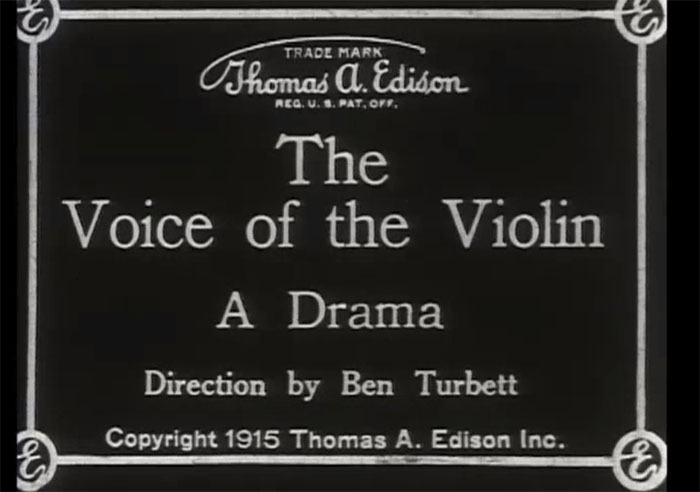

The Voice of the Violin

A Moving Picture Advertisement

for the Edison Diamond Disc

By Doug Boilesen, 2023

The Thomas A. Edison movie, The

Voice of the Violin, was a silent film created to promote

the the Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph in 1915.

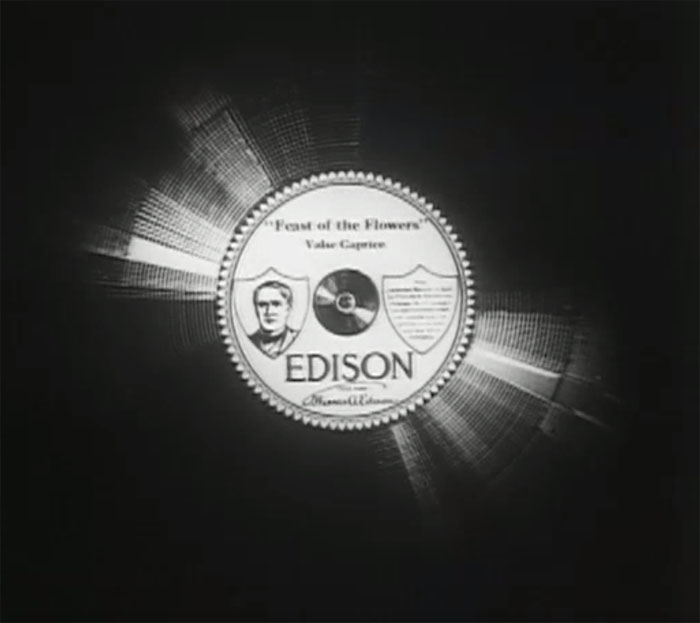

The stars of the show were the Edison

Diamond Disc Louis XV Model B-375 Phonograph (1912 - 1915) and

the Edison Diamond Disc record "Feast of the Flowers."

This movie was intended to be used by Edison dealers and shown

in local theatres as an advertisement for the Edison Diamond Disc

and its "Re-created" music of the Edison Records. The

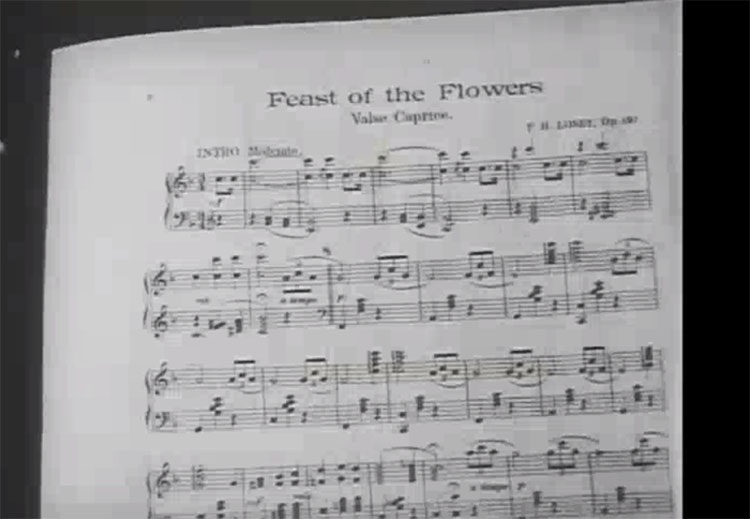

violin piece "Feast of the Flowers" was the Edison record

which also could have been played as part of the 'silent' movie

in addition to its important role it played in reuniting a family.

A movie of Anna Case performing

an Edison Tone Test may have also been part of the intended advertising

campaign for dealers of the Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph. Unfortunately,

that film has been lost. There is, however, a later 1926

Metropolitan opera Vitaphone short for the film "La Fiesta"

which Anna Case performing her song.

Source: The

Grammophon Museum

The following screenshots are from

"The Voice of the Violin." The 20 minute movie can be

watched using this link

to the Library of Congress digital copy.

Jack McLean playing

the violin and Marjorie playing the piano at the home of Herbert

McClean Sr., Jack's father.

Jack McLean buys

a Stradivarious with his inheritance money. "Only $7,000."

Jack returns home after

his purchase, shows Marjorie his new Strad, gives her the sheet

music "Feast of the Flowers" and they play a duet.

Herbert Jr. has lost

his legacy by gambling, has stolen bonds from his father, accuses

Jack of having taken the money. Herbert Sr. accordingly kicks

Jack out of the house.

Later learning the

truth that Jack's brother Herbert Jr. was the one who stole the

money, Herbert Sr. and Marjorie searched for Jack 'using every

known means," but with no success. In despair Marjorie suggests

they should take a break from the search. "Let's go to New

York. The change will do you good."

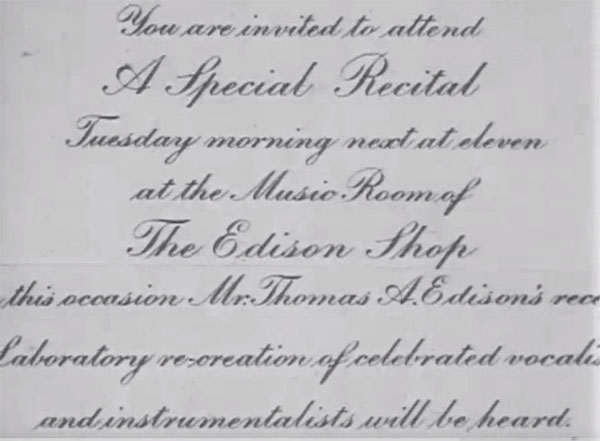

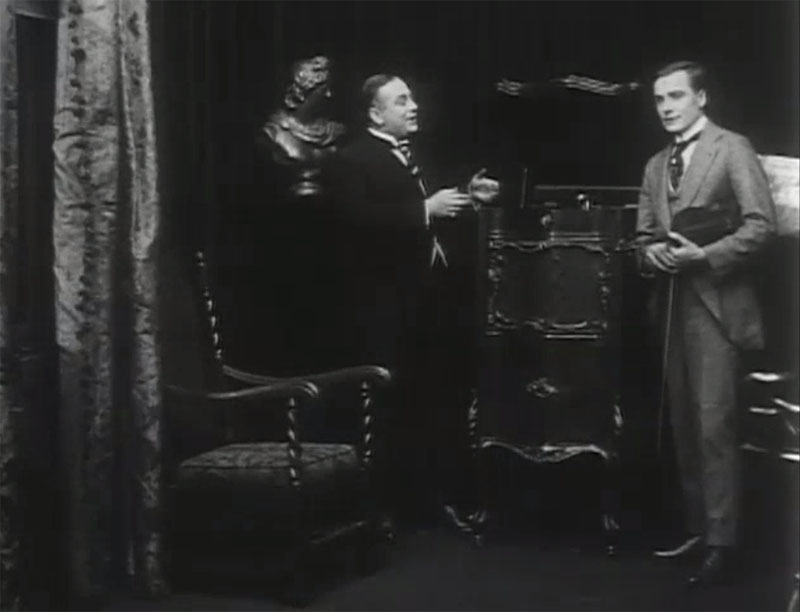

They go to New York

City where they receive an invitation to hear the new Edison Diamond

Disc Phonograph.

Herbert Sr. and Marjorie

accept the invitation and go to the Edison Shop for "A Special

Recital" which features its Diamond Disc Phonographs and

"No needles to change."

In the showroom of

the Edison Shop as the salesman prepared to a demonstrate the

Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph for Herbert McLean Sr. and Marjorie

they ask if he has the record "Feast of the Flowers?"

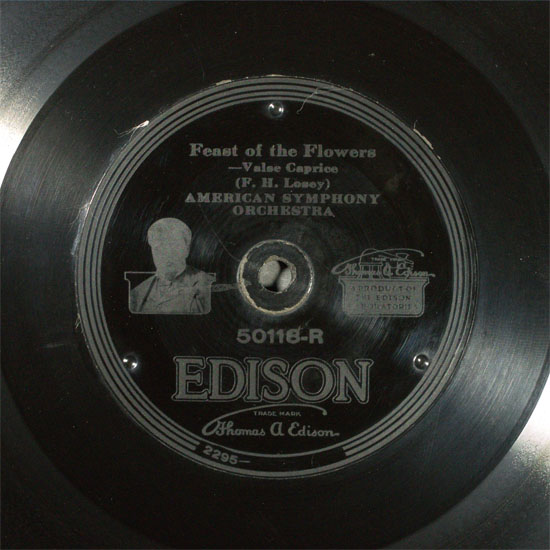

They do have that record

and the salesman puts it on the phonograph...and they listen.

LISTEN

to "Feast of the Flowers" performed by American Symphony

Orchestra, Edison Diamond Disc Record 50118-R (Source: DAHR

and UCSB Library).

Upon hearing the record

they each visualize Jack playing that song in their home and think

that it must be Jack playing on that record.

"Who is playing

first violin?" they ask. The salesman shows them the record.

"Can you tell me

where the records are made?"

"They are made at

the Edison Recording Laboratory at Orange, N.J."

They immediately drive

to the Orange, N.J. and the Edison Laboratory.

As they drive through

the factory entrance a movie intertitle explains: "These are

laboratories, not factories. The Edison Diamond Disc is the laboratory

re-creation of music, not a mere, mechanical reproduction."

At the same time Jack,

at the invitation of a chance acquaintance, is at the Edison Music

Room at Orange, N.J. listening to the Edison Diamond Disc Louis

XV Model A-375 Phonograph.

Herbert Sr. and Marjorie

come into the same room where Jack is listening. Jack's back is

turned when they enter but he hears their voices.

They see each other and

are quickly reunited as Herbert Sr. explains what has happened and

why they are there.

What a wonderful instrument;

what wonderful factories!" exclaims Jack.

Going to the window and

looking out at the factory buildings Jack says "In accomplishing

the actual re-creation of music by means of this new invention,

Mr. Edison spent four years of research work in acoustics and chemistry

and over two million dollars in experiments alone."

The camera again pans

the factory buildings from above, then stops on a building and tilts

down to a doorway below.

Jack, on the film's final

intertitle, says: "There he is now, Mr. Edison, himself."

The camera angle is now

street-level and from the doorway there is shown a one-second

view of Edison emerging from the door and taking a step.

"There he is now,

Mr. Edison, himself" followed by the one-second view of Edison

in "The Voice of the Violin."

The film ends after that

'one second' and the audience is left with the image of Edison and

his association with the Re-creation of music records and his new

Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph. There may have been more steps taken

but that is all that has survived so the "one second"

appearance has been assigned by Friends of the Phonograph

with the distinction being Edison's shortest appearance in any movie.

Although the movie was

a promotional movie for the Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph, audiences

probably enjoyed it as good entertainment -- especially for the

price.

CAST:

Marjorie played by Helen Fulton, 1894

- Unknown

Jack McClean played Pat O'Malley,

1890-1966

Herbert McClean Sr., played by Robert

Brower, 1850-1934

Herbert McClean Jr., played by Carlton

King, 1881-1932

(Source: Library of Congress and film

credits)

FACTOLA: The shortest appearance

of Edison in any movie is one second* and it was in the 1915 Edison

20-minute silent film "The Voice of the Violin." (*Note:

Edison's appearance is where the surviving copy of the movie

ends, but there may have been more which has been lost).

FACTOLA: A short drama film made

by Biograph Company New York in 1909 and directed by D. W. Griffith

was titled "Voice

of the Violin." Edison's movie has no connection with the

Biograph film and perhaps "The Voice" and "Voice"

were intentional naming distinctions (however, Wikipedia and IMDB

both identify the 1909 Biograph film as "The Voice of the Violin.")

See Phonographia's The

Phonograph, Sound and the Movies for more examples of how

the term "silent movies" needs some qualifications. Not

only did many sounds accompany these early moving pictures, a "variety

of sound strategies" were used. Large and small orchestras, organs,

pianos and living voices were the primary sources for providing sound

for the silent films. But there were also examples of the phonograph

inserting itself into a movie scene or being demonstrated by phonograph

dealers in movie theatres, one of those being "The Voice of the

Violin."

Helen Fulton,

1894 - Unknown.

David Bowers has the

best biography of Helen

Fulton who seems to have disappeared after 1918.

Movies where Helen Fulton

appeared:

"Vanity Fair," as Amelia

Sedley, 1915 silent film drama produced and released in October

by the Edison Company.

"The Voice of the Violin,"

as Marjorie, 1915, the Edison Company.

"The Unpardonable Sin,"

as Julia Landis, released on June 28, 1915 by World Film Corporation.

""The Coward's Code"

with Helen Fulton as Alice Gordon, 1916

"The Picture of Dorian Gray,"

as Evelyn, released July 29, 1915.

"Mercy on a Crutch," as

Mercy Tanner, released July 13, 1915. Thanhauser Film Corporation

Helen Fulton as Marjorie,

Voice of the Violin, 1915

""The Coward's

Code" with Helen Fulton as Alice Gordon, 1916

"The Picture

of Dorian Gray," as Evelyn, released July 29, 1915.

The following are a few other details

about Helen Fulton uncovered by Friend of the Phonograph

Wendy Shaw.

The earliest mention of Helen Fulton

as an actress was in 1910 (16 years old ) with Mrs. Fiske's Manhattan

Company.

In 1921, she was one of a group of

American women honored by The Italian Red Cross.

The last mention of her as an actress

was in 1917. In 1918, she was active in attempting to establish

a National Anthem Day and organizing a celebration in NYC for the

anniversary of the writing of the Star Spangled Banner (see below

for complete article in Musical America, September 28, 1918.

Helen Fulton is featured

in "Musical America," September 28, 1918 in an article

titled "Helen Fulton,

Whose Idea Set New York A-Singing the "Star-Spangled Banner."

Perfected Plans in Two Weeks -- Other Cities Eager to Follow Metropolis'

Lead" (Transcription

below - See original article here).

"Helen Fulton, Whose Idea

Set New York A-Singing the "Star-Spangled Banner."

"When the first observance

of National Anthem Day set everyone in New York singing the "Star

Spangled Banner" on the one hundred and fourth anniversary

of the writing of the song, Sept. 14, the public probably did

not realize that behind it all was just one person, the same indomitable

Helen Fulton who has already done a big bit for Uncle Sam. She

it was who in two weeks elaborated the plans which put a trained

singer in every theatre and motion-picture

house in the city to lead the audiences in singing the hymn, a

copy of the words of our anthem in every theater program and on

every table of every restaurant and in the windows of many shops,

such leaders as Harry Burnhart and L. Camilieri in the parks to

conduct gigantic community choruses, and Ann Fitaiu of Metropolitan

fame on the steps of the City Hall to sing the anthem from that

spot for the first time in the city's history. If it were not

for Helen Fulton, New York might never have waked as it is now

beginning to do to the fact the "Star Spangled Banner"

is one the world's most stirring songs.

As innocent of politics as a baby,

Miss Fulton took her courage in her hands and went to see Henry

MacDonald, director of tthe Mayor's Committee on National Defense.

"I showed him my plans,"

said Miss Fulton to a representative of MUSICAL AMERICA. "He

liked them and had me appointed chairman of the Mayor's national

Anthem Committee, and -- that's all. Everything went smoothly

and easily, except that I had to work pretty nearly twenty-four

hours a day to put it through, but then that's nothing."

Original Project

"My original project called

for an even larger celebrationj than that we actually had, but

the idea only occurred to me in July and it was not possible to

do everything I wanted to. However, future Anthem Days will give

us plenty of time and I expect to see my plans entirely carried

out by the end of the story.

"I wrote to Thomas F. Smith,

secretary of Tammany Hall and Congressman from my distgrict, and

asked him whether the fourteenth of September could not be set

as National Anthem Day by act of Congress. I thought it would

be splendid if we could initiate a nation-wide movement in that

way, but the time was too short -- not much more than a fortnight.

Large bodies move slowly and Mr. Smith thought we ought to try

to have National Anthem Day set by executive order instead of

by Congressional action, but even executive orders can't be commandeered.

Next year, however ---" Miss Fulton paused and the twinkle

in her eyes showed that her sigh was one of hope.

"I am particularly interested

in arranging and producing a pageant depicting the history of

the 'Star-Spangled Banner' and the customs and life of that period

in the development of the United States. Some time during November,

or perhaps as late as the holidays, that pageant is going to materialize.

Then I am preparing a patriotic movie to show the history of the

song and will have that shown in the moving-picture houses. The

stores have already begun to co-operate with us by putting a copy

of the words in every package they send out. Local Anthem Days

will continue to be observed as this first one was, with community

choruses and singing in the theaters and movie-houses."

"And Anthem Days that aren't

local?" Mis Fulton was asked. "Will there be any such

things?"

"It looks that way," she

replied with a laugh. "Hoboken, of all places, has been enthusiastic

about the scheme and the papers ask to have a day set by the Mayor

for observances like those we had here. I have received clippings

from Detroit that are just as enthusiastic and in fact the whole

country, so far as I can judge from the newspaper comments I have

seen, is eager to follow New York's example and will voluntarily

organize celebrations to impress on the popular consciousness

the importance of knowing our national anthem. There is no reason

that I can see why every man, woman and child in the United States,

American and foreign-born, should not be so familiar with the

words and music of the 'Star-Spangled Banner' that it shall in

time become the Allied Anthem to all nationalities residing in

this country. Wherever our flag is, there should our anthem be

also. In fact it should be known abroad too, just as the 'Marseillaise'

and songs of the other Allies are known here.

"I

am having several thousand postcards printed with one verse of

our song and the slogan, 'One Flag, One Country, One Anthem.'

At the side it says 'Learn Your National Anthem To-Day.' These

I am sending, at my own expense, to soldiers in the embarkation

camps. I'd like to make sure of every soldier 'over there,' and

every sailor too, having one, and I'd like to have translations

sent broadcast among our Allies, but -- where's the money to come

from? I'm no millionaire!

For Standard Version of Words

"And there's another difficulty

besides that of financial backing. Everybody has his own version

of the song. Some think we ought to say 'clouds of the fight'

instead of 'perilous fight' because when Key was an old, old man

and made an authograph copy for someone or other he made that

change from his own original text. But if we make that change

we must make others too -- for instance, 'on that shore' instead

of 'on the shore.' There's simply no stopping once you begin.

Personally, I prefer to stick to the words that were first printed

in the Baltimore Patriot, one hundred and four years ago,

for they afford a standard that leaves no room for controversy.

That is the version we have used and I expect it will be employed

by everyone who takes up the Anthem Day scheme.

"About the music, the situation

is far less satisfactory. The tune was edited by Sousa and Walter

Damrosch was only authorized for the navy and even if it had full

and unqualified government sanction we could not have used it,

for in getting things arranged at such short notice we had to

put up with whatever version our musicians happened to be in the

habit of using. I suppose

any version that might be chosen for the National Anthem Day celebrations

will probably be used everywhere, but it's going to be an awful

job to settle on one form of the tune and then put it in the hands

of all our musicians. Nothing

has yet been done about it by my committee; so far as we are concerned

the matter rests with the future."

"Have you seen anything that

would tend to show that your propaganda is bearing fruit?"

Miss Fulton was asked.

"Yes, I have indeed! Never

in my life have I heard anyone singing our national anthem as

they would 'Over There' or something like that, until Anthem Day

night when I was coming out of one of the theaters. There was

a dirty little ragamuffin on the sidewalk whistling the 'Star

Spangled Banner' just as gaily as he would a popular air.

"If every Anthem Day sets one

little boy whistling that tune I shall have been well paid for

my trouble, for what one little boy whistles another little boy

will whistle and so it will go" --

Miss Fulton waved her hand in a manner to indicate what is certainly

the case, that she has "started something." D. J. T.

Helen Fulton, who originated National

Anthem Day, Celebrated in New York on September 14, 1918. Musical

America, September 28, 1918 (Photo by the Bain News Service)

Despite Helen Fulton's efforts (and

many others), the "Star Spangled Banner" was not made the

official national anthem until 1931.

For a brief popular culture history

of the "Star Spangled Banner" with examples of sheet

music, phonograph records, "silent" and "talking pictures,"

see Phonographia's "The

Star Spangled Banner."

Last updated January 10, 2024

|