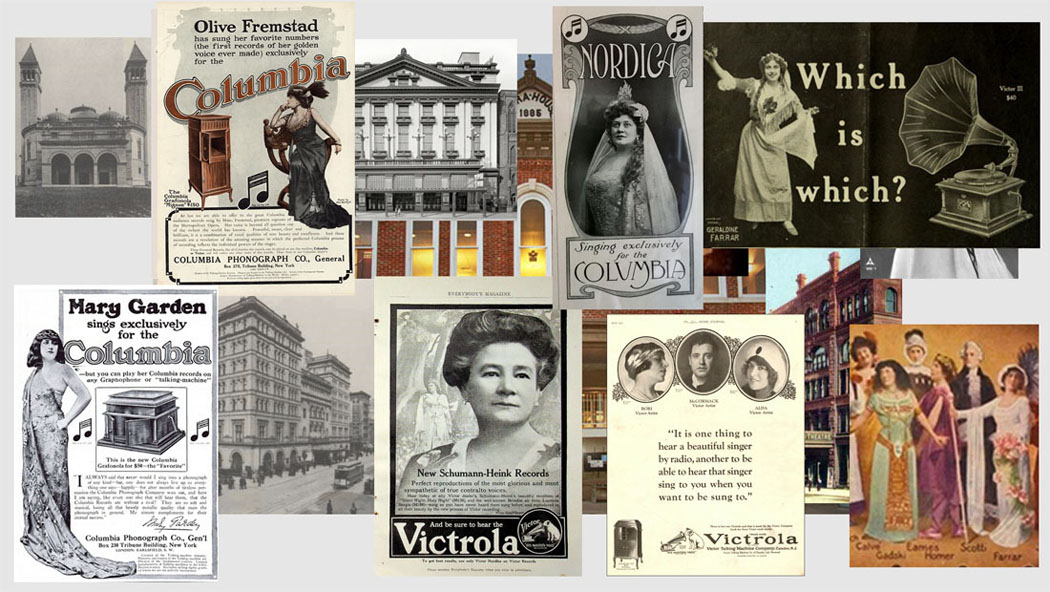

Willa

Cather's Prototypes Who Were Recording Artists.

FARRAR.

FREMSTAD. NORDICA. GARDEN. SCHUMANN-HEINK. BORI.

By Doug Boilesen, 2020

Willa Cather loved

opera and was a devoted patron of opera wherever she lived or

travelled. She had friendships with opera stars, understood the

world of opera, knew the challenges of being an artist in a consumer

world and of being a woman artist in male dominated domains, and

wrote multiple stories where a prima donna or an aspirational

artist was the central character.

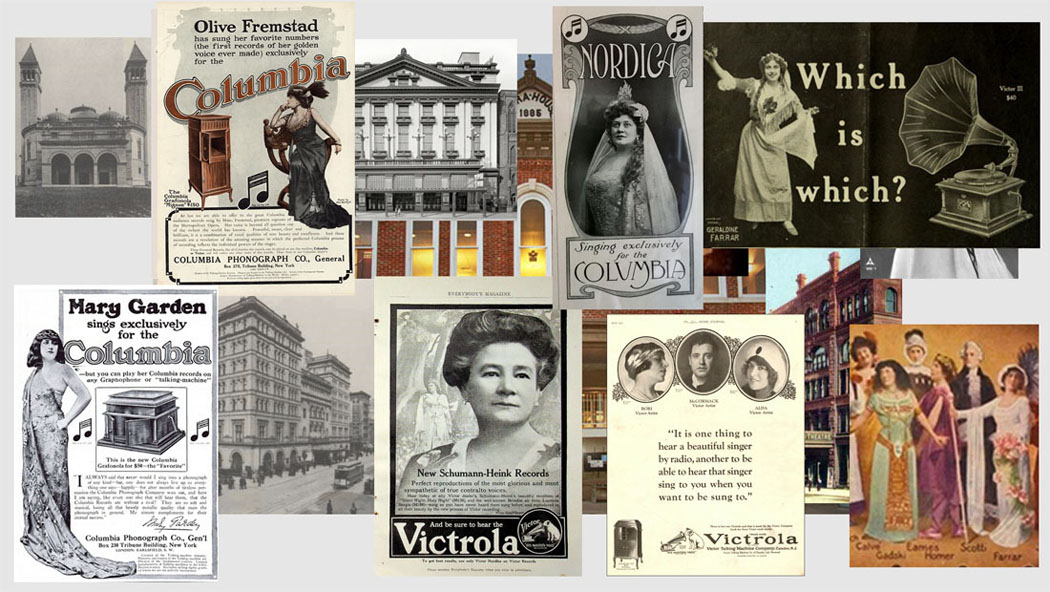

Six of Cather's opera

singing performers identified by scholars as

likely prototypes also made phonograph records and appeared

in phonograph ads. This gallery features those six prototype artists.

By appearing in popular

culture magazine ads the artists added their celebrity status,

artistic reputations, and the prestige of opera to promote key

phonograph industry themes; namely, that the world of entertainment,

highlighted by opera, was available to anyone, anytime and anyplace.

The "Stage

of the World', as it was advertised, could now be in your

own home where you would be more comfortable than in a theatre;

it was more convenient than going to a theatre, no expensive tickets

to buy, unlimited reperotoires, and always the best seat in the

house.

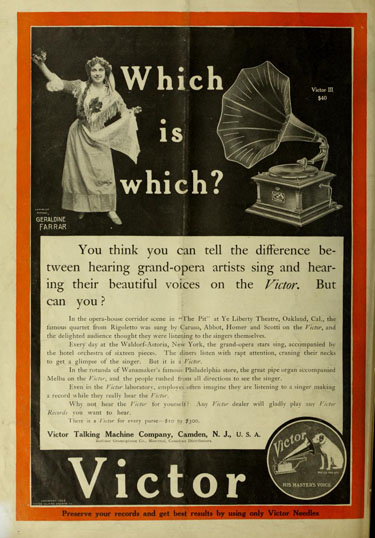

The

promotion of opera by the phonograph industry also had direct

and subtext ad campaigns suggesting recorded sound was the equivalent

of living artists. Victor's 1915 Munsey's ad summarized

it clearly: "The Victor Record of Farrar's

voice is just as truly Farrar as Farrar herself."

This page is an overview

with a few phonograph connected examples for each artist. The

majority of the examples are in the artist specific galleries

using the following links

to the six prototypes.

Geraldine

Farrar (one of the prototypes for Kitty Ayrshire in

Scandal and A Gold Slipper and interviewed by

Cather for her article Three American Singers).

Lillian

Nordica (prototype for Cressida Garnet in The Diamond

Mine).

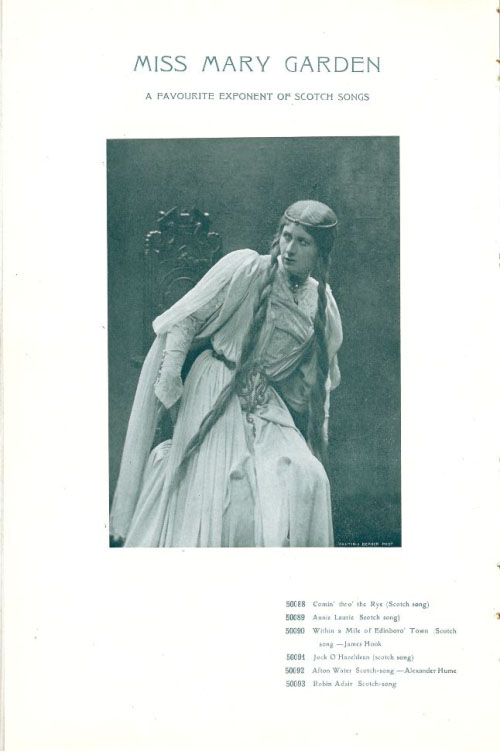

Mary

Garden (prototype for Eden Bower in Coming, Aphrodite!

and one of the prototypes for Kitty Ayrshire in Scandal).

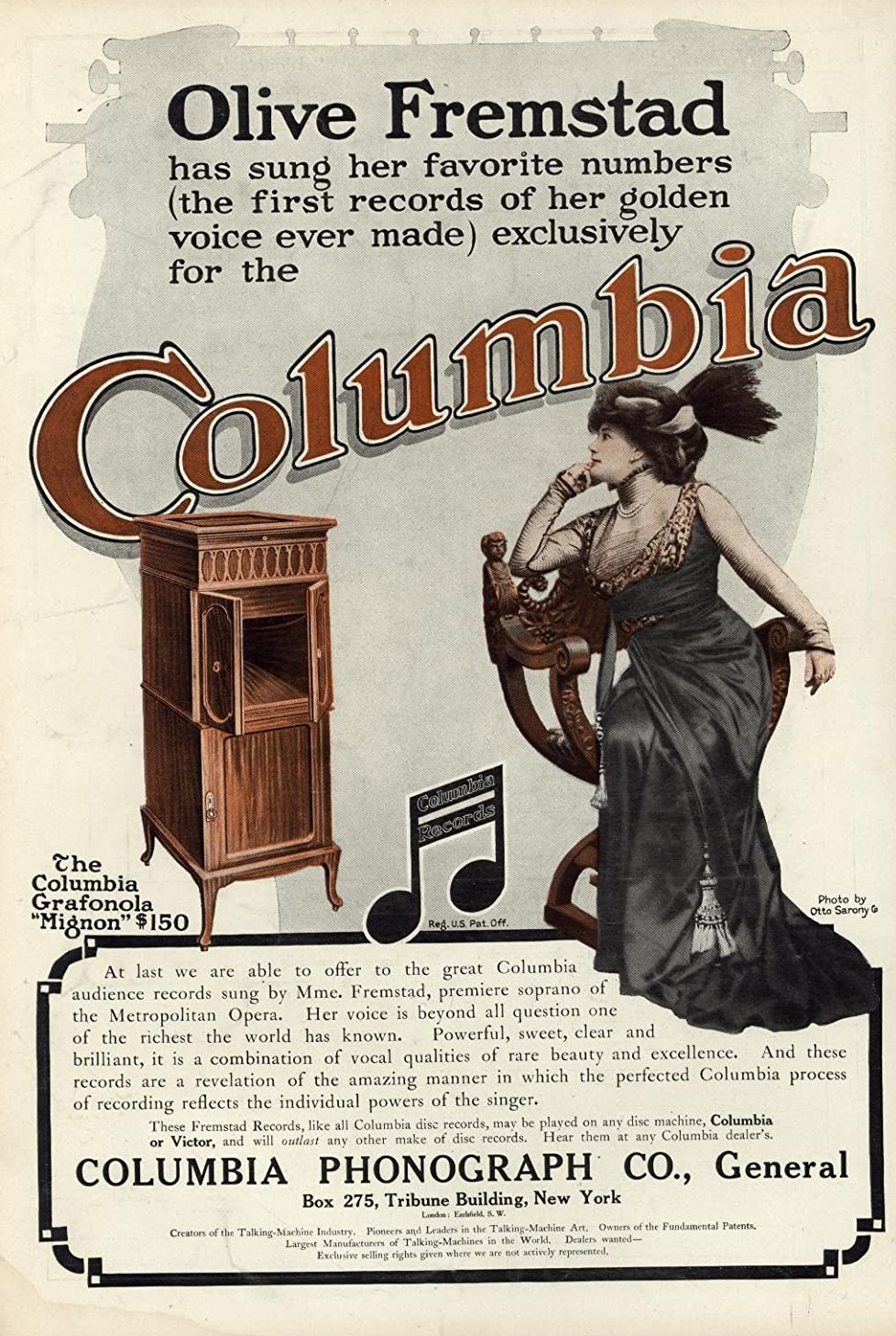

Olive

Fremstad (prototype for Thea Kronborg in The Song

of the Lark and interviewed by Cather for her article Three

American Singers).

Ernestine

Schumann-Heink (prototype

for "soprano soloist" in Paulís Case).

Lucrezia

Bori (prototype for "Spanish woman" in Scandal).

A Timeline of Cather

and the Phonograph

Cather's first collection

of short stories (The Troll Garden, 1905) were written

in the early years of the phonograph entering the home.

In the following decade,

when Cather was writing many of her opera and aspirational artist

stories e.g., The Song of the Lark (1915) and publishing

her collection of short stories Youth and Bright Medusa

(1920), the phonograph was becoming the definitive home entertainer.

Electrical recordings were introduced in 1925 and the prevalence

of radio in the 1930's would further redefine how the public experienced

sound.

The evolution of the

phonograph from 1900 to 1920 included advertisements made by six

of Cather's opera prototypes. Those ads also reveal aspects of

the new century's consumerism.

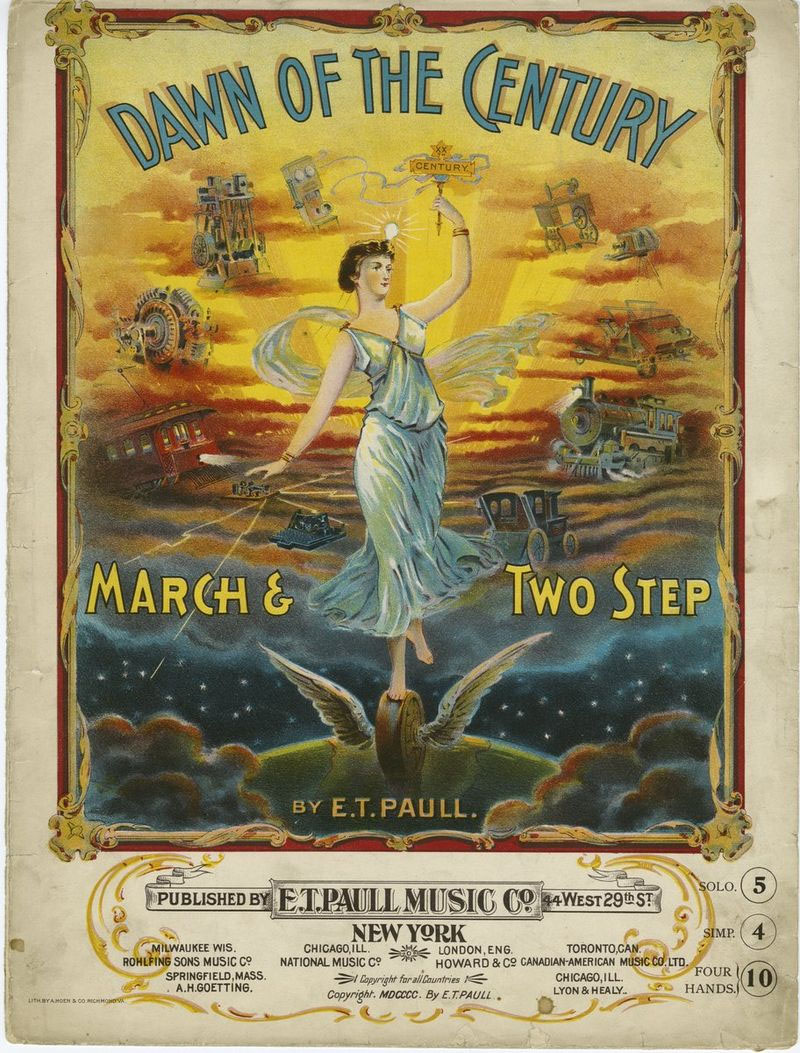

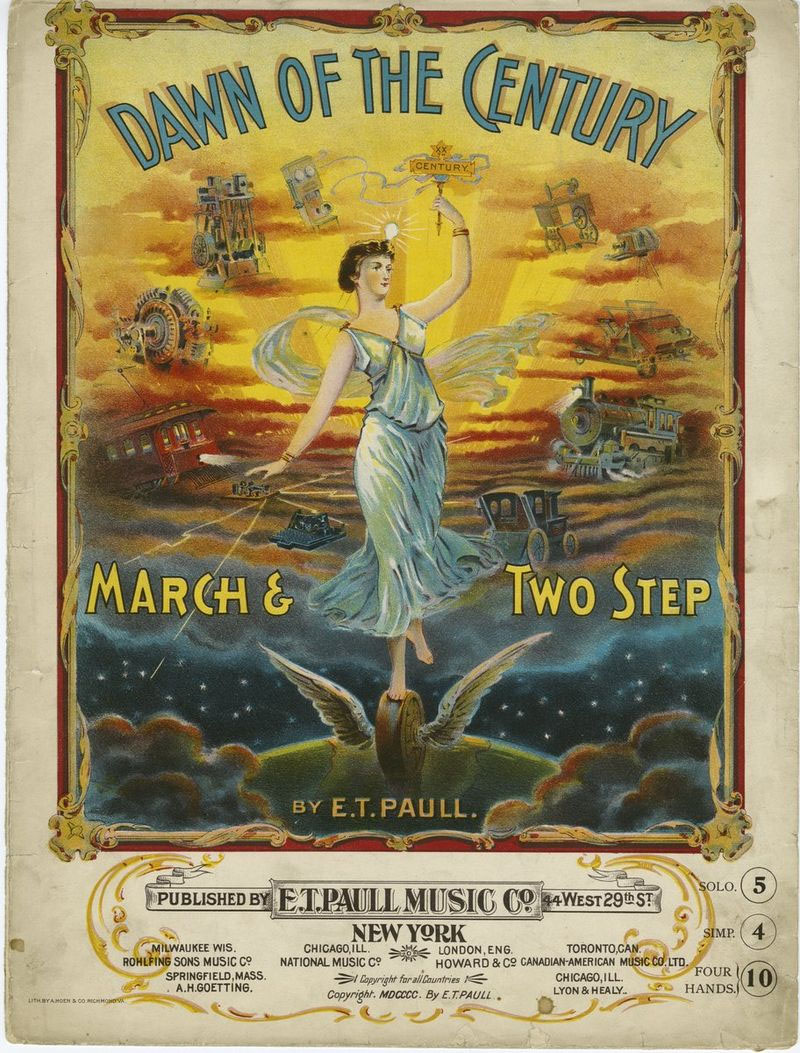

E.T. Paull - Sheet

music published by E.T. Paull Music Co., New York, 1900. (Sheet

Music from University of Indiana).

Opera records: Victor,

Columbia and Edison

In promoting opera

The Victor Talking Machine Company led the way with its advertising

campaigns featuring Caruso and "the greatest artists of the

world." Farrar, Schumann-Heink and Bori would all record

for Victor. Schumann-Heink also did five records for Columbia.

Columbia was a strong

competitor and promoted the exclusivity of their 'greatest artists

of the world" whenever they could. Nordica, Garden and Fremstad

would be featured Columbia artists. (3)

Edison didn't have

as many of the first-tier opera stars and seems to have been more

interested in advertising the technical accuracy of his phonograph

than promoting world-renowned artists. Even the repertory of those

Edison celebrity artists have been described as "confined

to hackneyed operatic arias and quasi-popular encore pieces"(3A).

Perhaps most revealing, the Edison business approach regarding

these recordings was said to have been "the flat statement

that the reproduction of operatic and symphonic music did not

represent a sound commercial proposition -- in America."

(3B)

Despite Edison's opinion

about the lack of commercial aspects for opera on records in 1914

Edison was making movies and an article in The Talking Machine

World stated that Edison was working every day to improve

the "Talkie-Movies" and that opera recording was important

to him.

"Opera

and drama for the poor workingman and his family for a nickel

is what we should have, and what we eventually will have,"

Mr. Edison said.

For over 40 years

Edison was also a major advertiser in the world of recorded sound

which did include 'grand opera' and the 'famous

artists' he did recruit.

Mary Garden recorded three records for Edison in 1905 and Lucrezia

Bori made thirty recordings for Edison between 1910 and 1913.

(3)

The Mapleson Cylinders

Recordings were made

between 1900 and 1903 by the Metropolitan Opera House's librarian

Lionel Mapleson using an Edison "Home" Phonograph purchased

for $30.00. Remarkably, one hundred and twenty-six cylinders are

known to have survived with Ernestine Schumann-Heink and Lillian

Nordica among those recorded voices.

Edison Home Model

A 1900.

Soprano Lillian Nordica,

with contralto Ernestine Schumann-Heink and tenor Georg Anthes

can be heard

HERE from the 'live" performance

originally captured on cylinder by Mapleson at the Metropolitan

on Monday evening, February 9, 1903.

The re-recording onto

78 rpm records from these cylinders was started in 1937 by William

H. Seltsam. For that story see "The

Mapleson Cylinders that Lived in Bridgeport: William H. Seltsam,

Lionel Mapleson, and Ghosts of the Golden Met" by Professor

Jeffrey Johnson, 2018.

Johnson's summary of

the meaning of those records hearkens back to a fundamental

theme newspapers included in their earliest articles about

Edison's new invention when Johnson wrote "These recordings

are audio sťances; they can summon ghosts."